AMBER HANSON: THE FLOAT ELEMENT

September 2025 -

Aura Space,

Braga, PT

*Curated by Amber Hanson and Lucija Šutej.

Float Element emerged as a co-curatorial project in conversation directly with the artist. The exhibition grows from changed gears, where in the spirit of Aura Space to inquire into objects and materials, we dwell into the process that guides the present exhibited series.

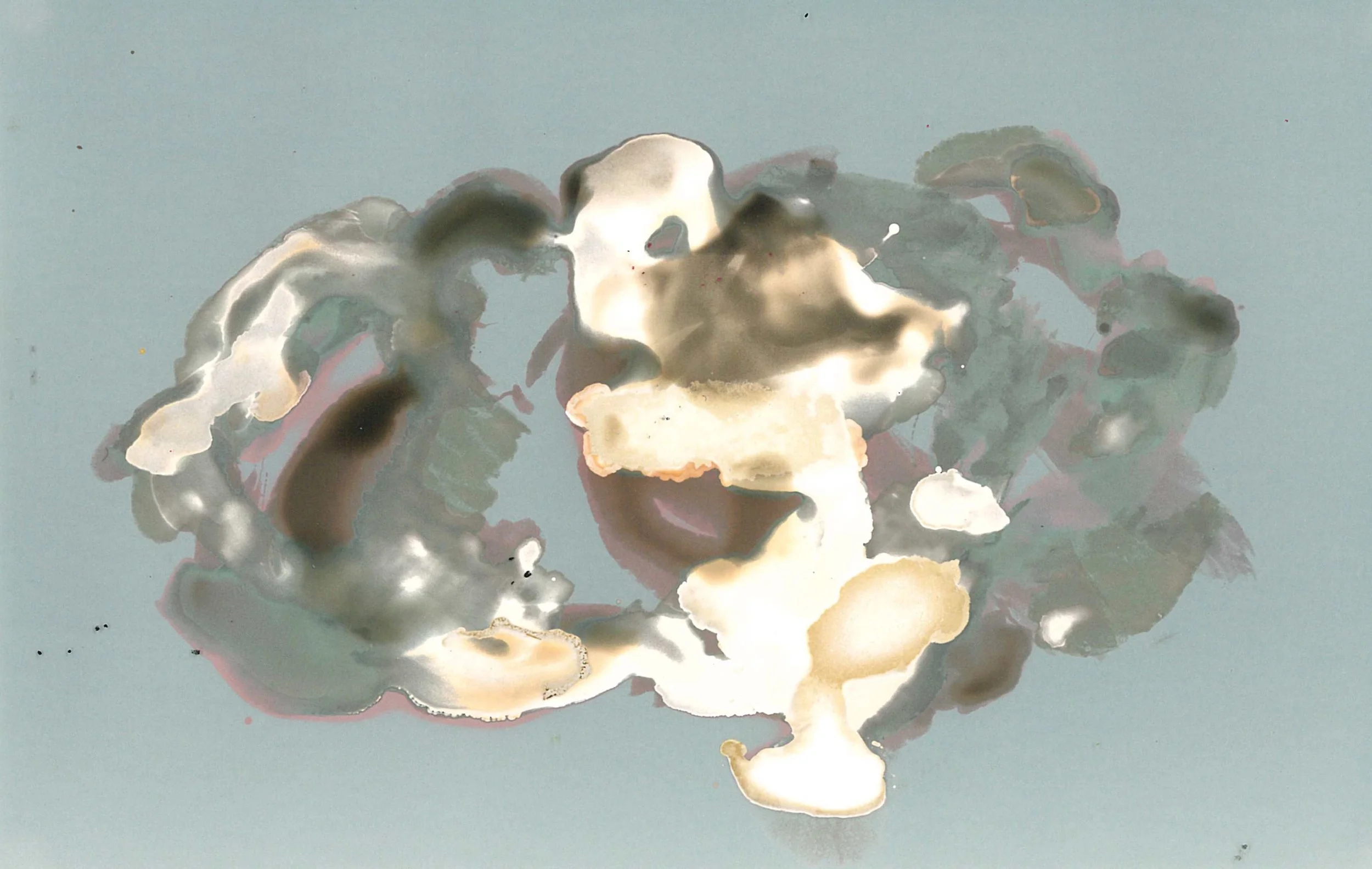

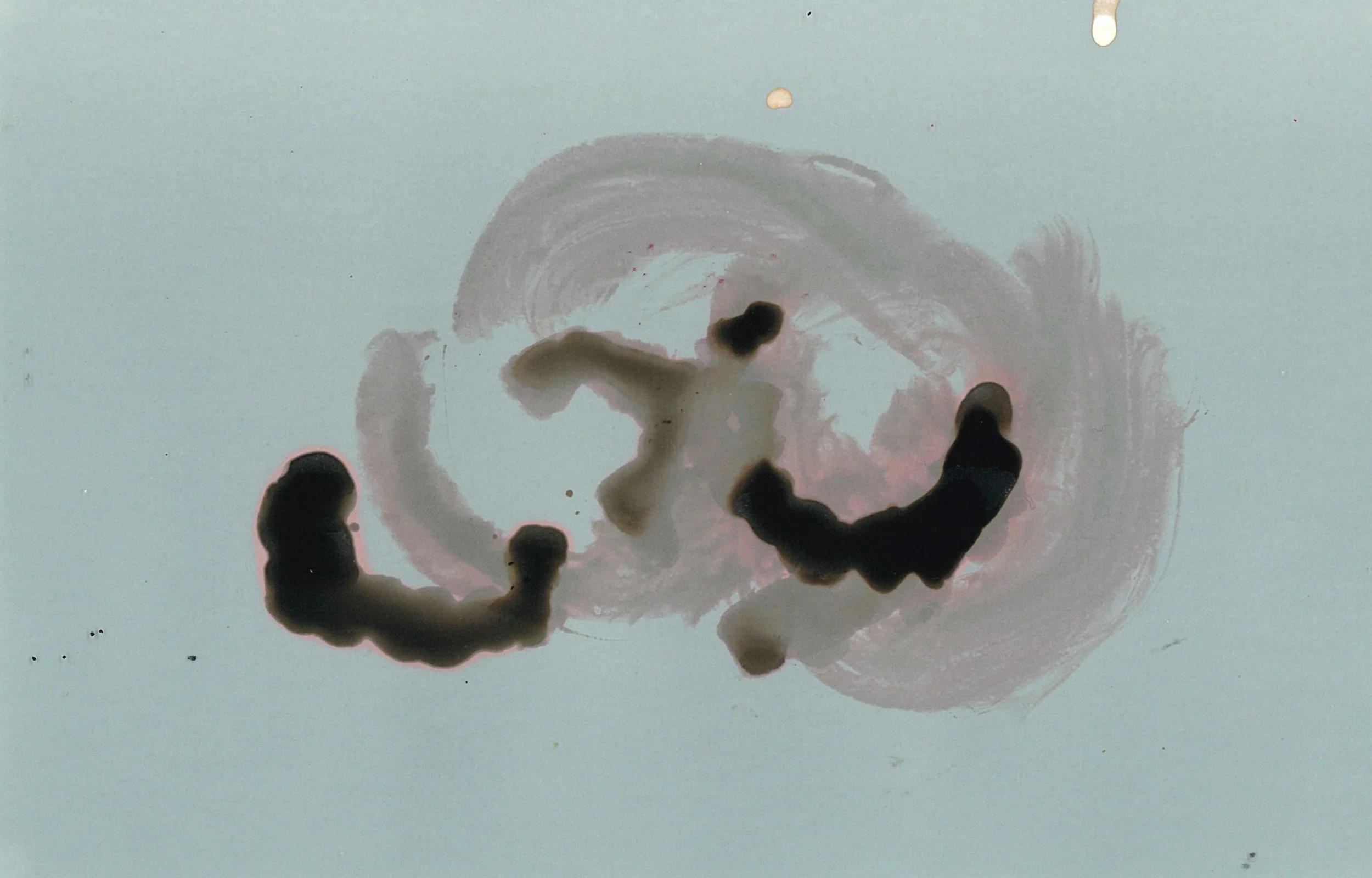

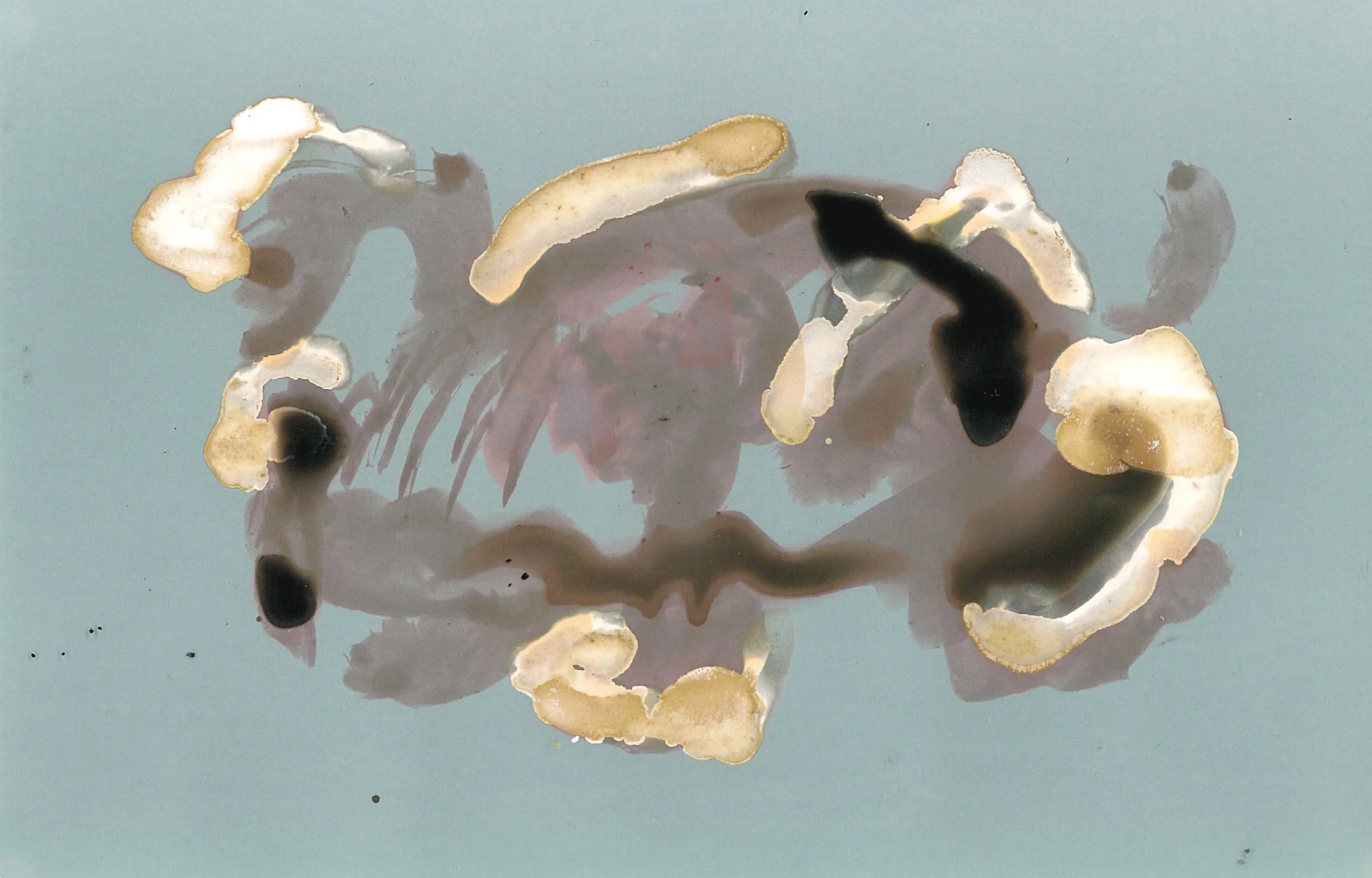

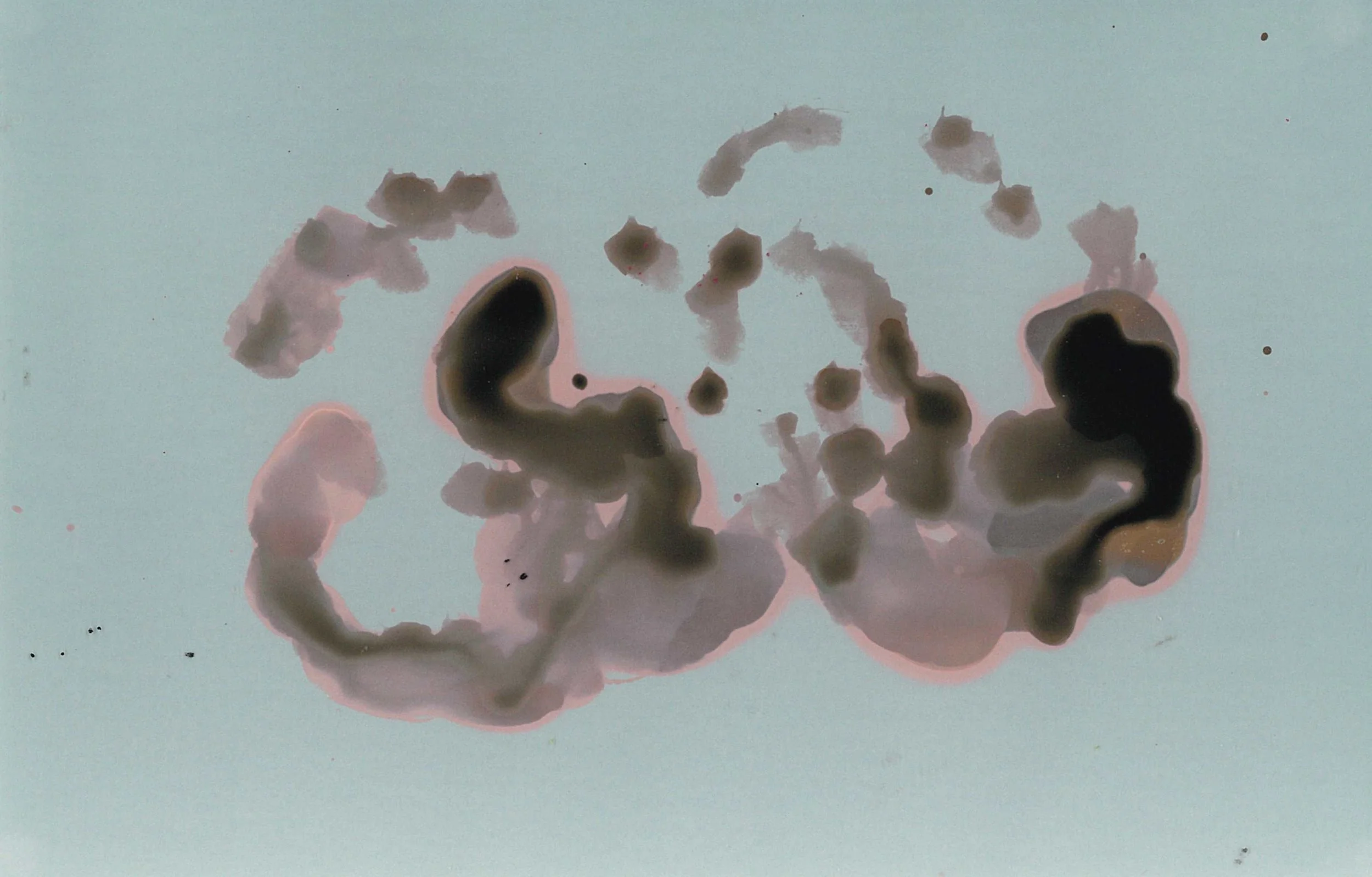

This series comprises multiple small-scale, paper-based works painted with traditional darkroom chemicals to depict clouds observed over England on separate days. Each piece is made not by capturing a photographic moment, but by painting with light-reactive solutions, traditional dark room developer, stop, and fix onto photographic light sensitive paper in an open format more akin to painting than printing. The developer activates with UV light, gradually darkening the paper over time. Stop and fix are applied at various stages, but not always in sequence, allowing some reactions to halt abruptly while others are left to evolve at differing speeds.

What emerges is a layered construction of atmospheric change: clouds rendering in real time, not as static representations, but as ongoing processes. As the chemical solutions are deliberately diluted, and the works sensitive to environments, they continue to shift during exhibition— deepening in tone, altering in texture, and sometimes fading or transforming depending on their proximity to windows or other UV sources.

In this way, the work becomes a collaborative choreography between time, light, and atmosphere. Only in complete darkness do they pause and remain unchanged. Never fully loaded.

AMBER HANSON

With Float Element Aura Space transforms into an open laboratory.

LUCIJA ŠUTEJ: When did you first consider photographic paper as a part of your painting practice? And what qualities were you interested to explore?

AMBER HANSON: I have been using dark rooms for photography for a long time, but I always liked the accidents and the chemical spills more than the imagery. I liked my actual photographic images clean and with the intention—so I swapped for digital photography in those cases. The darkroom still had a pull, and I started experimenting with chemigrams and photograms.

Over time I seeked to print my images onto the light sensitive paper still, so that they would change in different environments. To date, I tried many ways of traditional printing and transfer techniques onto paper, however qualities such as layers and texture building that emerged through the process were influential.

LŠ: What were the first chemicals and colours you applied - and how have they changed over time? Also how has the subject changed over time?

AH: At first with black and white photographic chemicals. Over time, I added chemigram favourites such as citric acid, bleach and varnishes which kept the images in a monochrome palette only able to manipulate hues and tints. Cyanotypes I would use as a quick and easy way to experiment with composition before using more sparse and expensive materials.

As the cyanotypes contained colour (blues) naturally, it would be dyed afterwards, however they still remained monochromatic. I was mixing different monochromatic palettes like a red, blue, black, brown and green swatch, applied on different layers and composition—which is something I’ve stuck to. But I have been able to develop areas of colour and my colour palette across all works has remained duo chromochromatic or monochromatic.

Content wise I think the subject has remained throughout but the compositions change, I flip between very large and small scales and from complex layers to very simple shapes.

LŠ: The application of time as an active agent/ co-creator in your work enables the work to slowly develop and change over time - never quite reaching the end result. What results have surprised you to date?

AH: The types of unintentional materiality that happens with this process is normally within the textures that occur over time. For example stopping the process usually strips the paper of its glossy coating or layering can fray the paper in parts. So, I try to anticipate this but also enjoy it as an after effect.

LŠ: Could you walk us through the current series dedicated to Clouds. Why interest in them?

And how did the series evolve?

AH: I wanted to make a piece that would also mirror my own interactions over time. And then look at those timelines in brackets of short periods of time creating and then middling time periods in the gallery space as the work changes in colour and hue. And creating a piece or several a day over a longer time period of months. The series is still ongoing and I have become more interested in the archiving of the photographer or participants over time, than the manipulation of time as a moment—as is traditional with photography.

LŠ: You speak of being more interested in the archiving of the photographer or participants over time, than the manipulation of time as a moment, how are the insatiable elements (time, chemistry) altering the perception of the archive for you?

How does it expand on the idea of photography as an archive that is permanent?

AH: I’m not more interested in the photographer than the situation or material, I think what I meant is that we grew up in a generation that was accepting of the knowledge that photography is deceiving but so true to life. We were aware that photography was a lie, images are manipulated, one angle can hide a thousand more, etc. It always shocked me that education tried to tell us this obvious fact like it was new. But that is a symptom of growing up with the internet, we are naturally sceptical I think.

And so to look at photography as a collection of some kind, you have to look at it re-expanded in a space or a time or in a more 4-dimensional way. It feels very different to look at a curated archive of photographs you can relate to, to ones of situations that you can only imagine.

So, making something material based, to be read materially I think means that it can be read by everyone, as everyone is having a tactile physical experience. This isn’t a permanent archive either.

It’s more that I want a photographer or artist's intentions to be more forthcoming—I like art that tells me what it is.

LŠ: How is the process contributing to the understanding of the notion of an archive?

AH: I think just focusing attention on an archive not being permanent and to draw more understanding or relation to an artwork away from the artist and more towards material. But I think those are just my own frustrations with the limited ways that art is seen. And with the slowness of academics and the process of archiving.

I think the destabilising of archives is as important as building them in the first place, to slow down a moment, not to try and capture it frozen. Watching an image change incrementally over time in tiny adjustments forces you to think of the material and its environment as a factor in this change.

LŠ: What are your plans on the expansion of the series?

AH: I want to find a way to digitally interact with the piece in a curatorial way, whilst retaining the real-world/time element of the piece changing in the physical space. This does change the nature of the work but not the context.

I have been playing with creative coding solutions and web-based publishing tactics to try and think about this more. But I will continue to paint them for a long time I think.

Amber Hanson Rowe is a Cambridge based artist and researcher working across speculative media, digital systems, and material image-making. Her practice spans moving image, web-based installation, and chemical painting, exploring how technologies reshape perception, authorship, and memory. Drawing from post-internet aesthetics, archival logic, and open-world systems, she builds works that remain evolving living documents responsive to interaction, environment, or time.