AKI INOMATA

Portrait, Photo: Nomura Sakiko

Aki Inomata graduated with an MFA in Inter-media Art from Tokyo University of the Arts in 2008.

Focusing on how the act of “making” is not exclusive to mankind, AKI INOMATA develops the process of collaboration with living creatures into artworks.

Her recent exhibitions include “Bangkok Art Biennale 2024” (BACC, 2024), “Forest Festival of the Arts Okayama: Clear-skies Country”(Nagi Museum of Contemporary Art, Okayama, Japan, 2024), “Roppongi Crossing 2022” (Mori Art Museum, 2022), “Aichi Triennale 2022” (House of Oka, 2022), “Broken Nature” (MoMA, 2020), “The XXII Triennale di Milano” (Triennale Design Museum, 2019), “Thailand Biennale Krabi 2018” (Krabi city, 2018), “AKI INOMATA, Why Not Hand Over ‘Shelter’ to Hermit Crabs?” (Musée d’arts de Nantes, 2018).

Her works are included in many collections, including those of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Art Gallery of South Australia, the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, and the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art.

LUCIJA ŠUTEJ: When and how did you shape an interest in interspecies collaboration?

AKI INOMATA: I grew up in the heart of Tokyo, far from nature. Maybe because I didn’t have easy access to it, I became especially fascinated by animals I saw on TV and in picture books. Their distance from my everyday life only made me more curious about them.

At the same time, I was fortunate that my elementary school was located inside a university campus, where I could encounter all kinds of creatures. I used to pick wild plants and catch crickets and dragonflies to bring home. The contrast between the city’s concrete and the soil of the wooded campus shaped my earliest experiences.

My interest in working with living creatures began with Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs? (2009–). While studying at art school, I tried bringing natural elements into the artificial space of the gallery. In one piece, 0100101, shadows cast by ripples on water spread throughout the room. These projects came from a discomfort I felt with the highly controlled environment of urban life.

0100101, image courtesy of the artist.

But over time, I started to realize that even the natural elements I brought into the gallery were still digitally controlled—it felt as if I was just recreating the very structures I had been questioning. That realization led me to a period of deep reflection.

It was around that time I took part in No Man’s Land, an exhibition held at the former French Embassy in Tokyo. There, I created Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs?, which became a turning point and led me toward interspecies collaboration.

Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs?

LŠ: The work Why Not Hand Over a Shelter to Hermit Crabs? is an ongoing series/ body of work- how have you experienced its evolution?

AI: One of the most memorable experiences during the creation of Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs? was designing the shells.

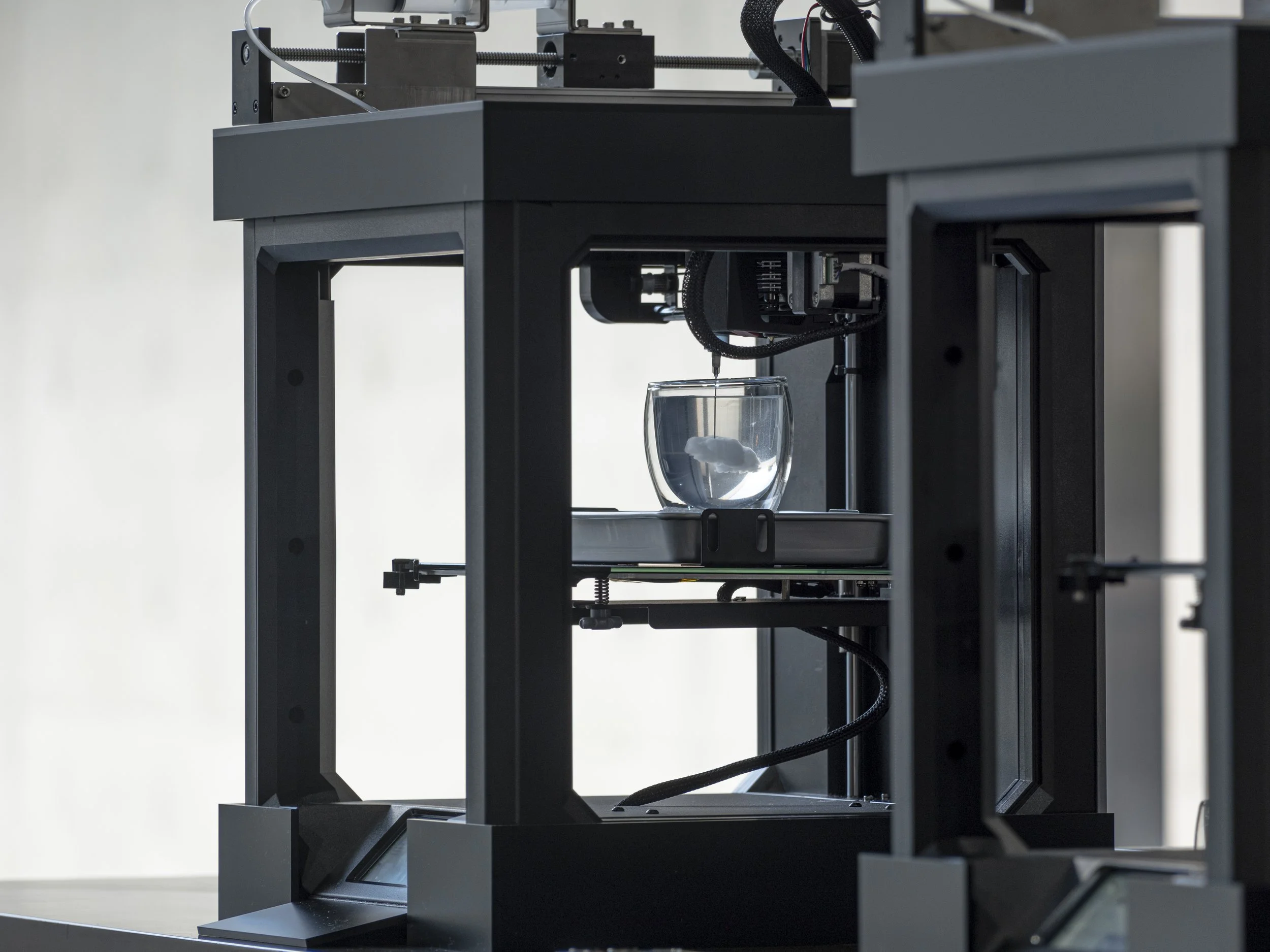

I used a 3D printer to produce the shells, each incorporating the form of a city from around the world. The real challenge, though, lay in shaping the inside to encourage hermit crabs to move in. I tried many different designs to see which ones they would actually choose.

At first, I tried simple spherical shapes, but the hermit crabs showed no interest. I had heard that some of them use plastic bottle caps as makeshift homes, so I tested that idea as well—but they still preferred natural shells. Through repeated trials, I began to understand that they favored certain features: spiral-shaped interiors, smooth surfaces, and specific thicknesses. I spent many days observing their behavior, testing new designs, and recording their reactions—whether they accepted or rejected each prototype.

Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs?

Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs?

Hermit crabs live in their “umwelt”—a species-specific perceptual world—so they behaved in ways I couldn’t predict. Even when I thought I had designed the perfect shell, I would sometimes find it discarded in the water the next day. Their behaviors constantly challenged my assumptions, pushing me to rethink my approach.

The process felt like a kind of dialogue—an ongoing exchange where I adjusted my designs in response to their choices. In the end, it produced a set of shells that brought together the solid, geometric language of architecture with the organic, evolved forms of natural shells.

This experience deepened my interest in living creatures. Rather than completing everything alone, the organic evolution of design through trial and error and dialogue with others—especially with living beings—has greatly shaped my artistic approach.

Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs?

LŠ: How and have the questions changed for you across the complex relationship between architecture, and society? The shells of the crabs present fragments of different urban landscapes - we recognize Bangkok, Tokyo, Santorini, to name just a few. How do highlights on specific cities reveal or add to the different dimensions of the work?

AI: My creative starting point for Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs? was viewing the grounds of the French Embassy as a unique situation. As the Japanese word yadogari (宿借) suggests, the characteristic of hermit crabs as beings that “borrow” shelters deepened my inquiry.

During the exhibition at the embassy, several visitors commented that the hermit crab in the work seemed like a reflection of themselves. This became a strong motivation to continue the project. Afterwards, through the hermit crabs, I began to engage deeply with themes such as movement, place, and the interchangeability of identity.

I explored the overlap between shelters as architecture, animal behavior, and metaphors like social borders and migration, evolving my questions within these complex relationships.The shells shaped like cities originated from the No Man’s Land exhibition at the French Embassy, which was the starting point for this work. The embassy grounds, located in central Tokyo, were once French territory. When the embassy relocated, the land was returned to Japan, but after 60 years, it was returned to France again. This story inspired me.

At the same time, hermit crabs grow by moving to new shells, drastically changing their appearance through this “house changing.” When a hermit crab moves, the shell may look like part of the crab itself, but it is actually a “borrowed” object. Similarly, a person’s nationality seems inseparable from themselves but may not be. This work visually explores themes of immigration, migration, and the fluidity of identity. The hermit crab’s repeated moves from one city-shaped shell to another echo the experiences of migrants and refugees. The work reveals that identity is not fixed but constantly changing.

LŠ: 3D printing techniques enabled reimagining and replication of the shells of the crabs. As you gradually added CT scans to the process—a new layer to the work was achieved. How or did these experiences reshape for you the understanding and relationship between technology and nature's own design?

AI: Incorporating CT scans into my creative process deepened my understanding of natural forms and structures. Initially, I used a 3D printer to recreate hermit crab shells, but CT scanning allowed me to capture the intricate internal shapes of natural shells with remarkable precision.

Through this detailed insight, I discovered that the shell’s internal spiral and its smooth inner surface play a crucial role for hermit crabs. They select shells carefully, focusing not just on the exterior shape but especially on the internal structure to ensure their survival. This experience transformed how I view the relationship between technology and nature. Technology became more than a means of replication—it became a tool to uncover nature’s profound design principles.

I came to appreciate how living beings’ behaviors and choices result in exquisitely refined designs. The importance of the spiral appears repeatedly as a natural pattern in many of my later works, including beaver-gnawed wood and cloud formations.

LŠ: How do you see it developing in the future. what questions do you see and will guide you as the next steps?

AI: This work holds a position close to a life’s work for me, and I plan to continue creating shells representing various cities. While the work itself won’t change significantly, I will keep exploring themes of immigration, migration, and the fluidity of identity by selecting different buildings and cities.

As the world around us changes, I believe the interpretation of the work will also evolve to reflect those shifts. For example, in the world of hermit crabs, stronger individuals sometimes steal shells from weaker ones—a form of competition over shelter. This behavior parallels borders, movement, and migration. From hermit crabs, we can learn that identity is fluid and constantly changing, rather than fixed.

The crab’s body and shell are separate, and while we tend to identify them by their shells, hermit crabs frequently exchange shells, making individual identity hard to pin down. For this work, I created multiple 3D-printed shells symbolizing cities from different countries, which the hermit crabs exchange among themselves. Their actions form the core of the piece.

LŠ: The work girl, girl, girl — redefines textiles pieces from different garments. It would be great to hear the story and research behind the work. And how has this work influenced the direction of Passing her a piece of cloth? The works also lead towards the research of Shibori Tie-Dye process.

AI: This work, which imitates the patterns on moth wings using the shibori dyeing technique, began by studying the rules hidden in biological design. I discovered that the wing patterns form through the diffusion of a certain protein, which can be described by a mathematical model known as the diffusion equation.

Installation view at Aichi Triennale 2022, AKI INOMATA, Shibori (tie-dye) round fan with wing pattern of the fungus-feeding bagworm / Shibori (tie-dye) round fan with wing pattern of the wood boring bagworm, (2022). ©︎ Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee. Photo: ToLoLo studio

Installation view at Aichi Triennale 2022, AKI INOMATA, Shibori (tie-dye) round fan with wing pattern of the fungus-feeding bagworm (2022). Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee. Photo: ToLoLo studio

Passing her a piece of cloth. Installation view at Aichi Triennale 2022, AKI INOMATA, Passing her a piece of cloth (2022). © Aichi Triennale Organising Committee. Photo: ToLoLo Studio.

Passing her a piece of cloth.

Researchers introduced me to the concept of a “grand plan” — a common set of rules underlying all moth wing patterns. Meanwhile, Arimatsu Shibori—a traditional tie-dye technique practiced for 400 years in the town of Arimatsu, where I stayed during the International Art Festival Aichi 2022—is a technique of tying or stitching fabric before dyeing, then untying the threads to reveal a variety of unique patterns.

What I found especially in common between moth wing patterns and shibori is that no two patterns are ever exactly alike. This connects to my long-standing interest in creativity emerging from unpredictable chances. Unlike the human desire to control everything, shibori embraces chance, generating unexpected beauty and forms—a concept I call “creativity of chance.”

Biological systems function similarly—no two moth wings are identical. This experience reaffirmed the importance of accepting that humans do not control everything and of encountering creativity that allows nature to take the lead. My work explores the intersection where the natural unpredictability of biological systems intersects with human craftsmanship.

LŠ:You are currently working on Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky; where clouds are essentially created through 3D printed milk, which is placed in the water. Your website defines the work as: “...the project emerged in response to the evident transformations in the global environment caused by the pandemic, … to realize that ‘today will never be the same as yesterday”.What truly captures the work and alerts the audience is temporality. How do you see the work speaking to present times of ecological and social uncertainty and challenges?

AI: The work I have been developing over several years, Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky, began when I noticed the shifting clouds outside my window during the COVID-19 pandemic and realized that “today is never the same as yesterday.” This piece features 3D-printed milk “clouds” suspended in water, whose defining characteristic is their fragility.

It raises questions about the irreversible nature of time and the sustainability of the natural environment.

The artwork continuously changes shape and ultimately disappears when viewers drink the water. This sense of time—that the piece is not fixed but changes, is consumed, and eventually disappears—marks a new direction in my work. Another key aspect is that viewers can physically ingest the water. This expands the usual focus on visual experience in contemporary art to include engagement through taste as well.

By engaging both visually and gustatorily, viewers immerse themselves in the moment and become deeply aware of the work’s unique, ephemeral nature as it disappears.

Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky. Photo: Asaoka Eisuke

Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky. Photo: Kenryou Gu

Responding to the profound environmental, social, and other uncertainties of our time, this work engages with these themes. While our culture often encourages us to focus on the future and productivity, Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky invites us to perceive significant differences within seemingly repetitive daily life and to pay attention to the present moment.

The work also invites ecological reflection from the audience. It encourages reflection on how humans, as part of nature, might confront the uncertainties of our era, encouraging us to move beyond an anthropocentric perspective.

Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky. Photo: Asaoka Eisuke

Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky. Photo: Hayato Wakabayashi

Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky. Photo: Hayato Wakabayashi

Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky. Photo: Kenryou Gu

Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky. Photo: Hayato Wakabayashi