ADRIAN PEPE

Portrait, courtesy of the artist.

Adrian Pepe is a fiber artist based in Beirut, Lebanon. His artistic practice is an ongoing exploration of process and materiality. Through his work, he interweaves elements of nature and culture, creating objects that serve as tools for fostering an open dialogue on materiality, our evolving cultural landscape and present conditions. His creations are laden with artistry, perspiration, emotions, mythologies, and symbolism; hybridized skins in the form of wall hangings, installations, and soft sculptures, each narrating a multiplicity of histories, cartographies, and cosmologies.

LUCIJA ŠUTEJ: What drew you to wool as a medium and a vessel of knowledge?

ADRIAN PEPE: Initially, it was its neglected status in the region that drew me in; its disuse revealed something about shifting values, forgotten systems, and what we choose to discard. Wool holds the animal’s presence and absence. Working with it became a way to think through interspecies intimacy, cultural memory, and the afterlives of utility. The sheep, as a species, sits at a charged intersection of biology, mythology, religion, and domestication, both a witness and a vessel of human culture.

LŠ: Through your work, what have you learned about the Awassi sheep and the qualities of its wool? How does its materiality shape your work?

AP: The Awassi is a fat-tailed breed native to Western Asia, suited to arid environments. Its wool is coarse and dense, considered carpet-quality, and also used in stuffing. In Lebanon alone, there are over half a million sheep that produce thousands of tons of wool each year, most of which is discarded due to a lack of demand and inadequate processing infrastructure.

I work with this surplus, performing all treatments in the studio. The hands-on nature of the process—shaving, cleansing, washing, willowing—generates a closeness to the material and its origins. Its abundance allows for scale, resulting in some sizable works I’ve produced in the past. The wool doesn’t behave as a neutral medium. It’s versatile. It resists, expands, and responds.

Images of the process of wool treatment - from sheep shearing to wet felting (below and above) . Courtesy Adrian Pepe.

LŠ: What lessons were shared with you by the local shepherding communities?

AP: The shepherds offered a new perspective rather than instruction. Most of what I learned was related to systems of care between the shepherd and the sheep, as well as between the sheep and the land. Care is continuous, unspoken, and embedded. I learned to consider maintenance as a form of knowledge.

Courtesy Adrian Pepe.

LŠ: How do you see wool as a living archive?

AP: Each fleece holds a micro-ecology. Seed, dust, parasite, scent—all embedded and entangled in the fiber. From a strand of wool, we can read terrain, movement, and sustenance. The animal body becomes an archive of its landscape. It carries traces of what fed it, what grazed it, what touched it.

But wool is also a symbolic archive. It holds centuries of meaning, ritual, economy, and myth. Entire systems of trade, value, and belief were built around it. In a way, human history was written on its back. Working with wool becomes an act of listening not only to the land, but to the narratives we’ve spun through it.

LŠ: The production of wool often dominates sheep-based crafts; however historically different parts of the animal were used for different objects and artefacts.

AP: Historically, every part of the sheep had a role. Bones, skins, gut, and wool were used in tools, garments, vessels, instruments, and rituals. Today, that total use has fragmented. My work often starts with the inedible or the discarded. I am interested in what happens when we reinsert these fragments into conversation, not to reconstruct tradition, but to explore how meaning circulates between flesh, tool, and gesture. In a way, the work speculates on what we’ve outgrown and what remains.

LŠ: Can you share your research behind The Gilded Fleece and the relationship between tool and treasure?

AP: The Golden Fleece is a myth about desire, pursuit, conquest, power, and value. I was drawn to how a sheep’s fleece became a symbol of a seemingly impossible goal, which could stand for any valuable or coveted object. That idea isn’t just symbolic, it’s economic. The word capital comes from caput, Latin for “head,” and was used in reference to heads of cattle, the original markers of wealth and exchange.

In this work, I used real sheepskins, stitched and gilded on the flesh side with 24-karat gold leaf; the incorruptible applied to the corruptible. The side that’s usually hidden, protected, and becomes the surface of display. The soft interior is exposed. I wanted to highlight this collision between labor and ornament, utility and mythology, survival and fantasy.

The Gilded Fleece, image by Edmund Summer.

LŠ: Your recent work, The Utility of Being, is a site-specific installation exhibited in a former slaughterhouse. Could you share with us the story behind the work?

AP: The work was developed for a former slaughterhouse in Sharjah. I gathered discarded Awassi pelts, cleaned and treated them, then inflated them into visceral, tubular forms. These inflatables, suspended from the same hooks that once held carcasses, traced a new anatomy across the space. I was thinking about what it means for the biomass of the animal to return to this space of both demise and transition. A confrontation. The work touches on the systems of meat production, but also on breath, skin, pressure, and vulnerability.

LŠ: How did the history of the location influence the piece?

AP: The slaughterhouse carried its own scent memory. The architecture spoke. I didn’t want to overwrite its history, but to activate its residues, to let the space and the material converge in a confrontation, as the reanimated, breathing biomass returns.

LŠ: In one of your prior interviews, you also spoke of the research into different cultures creating inflatable devices from animal parts. Did they influence how you treated the art pieces?

AP: Yes. I looked into how animal bladders and skins were historically used for flotation, for sound, for transport. From Arctic regions to the Middle East, these techniques existed. One example is the habban, a traditional bagpipe still used in parts of the Arabian Peninsula, made from animal skin and reed. These ancestral technologies informed how I approached skin as a membrane, as a chamber, as a vessel for air and resonance.

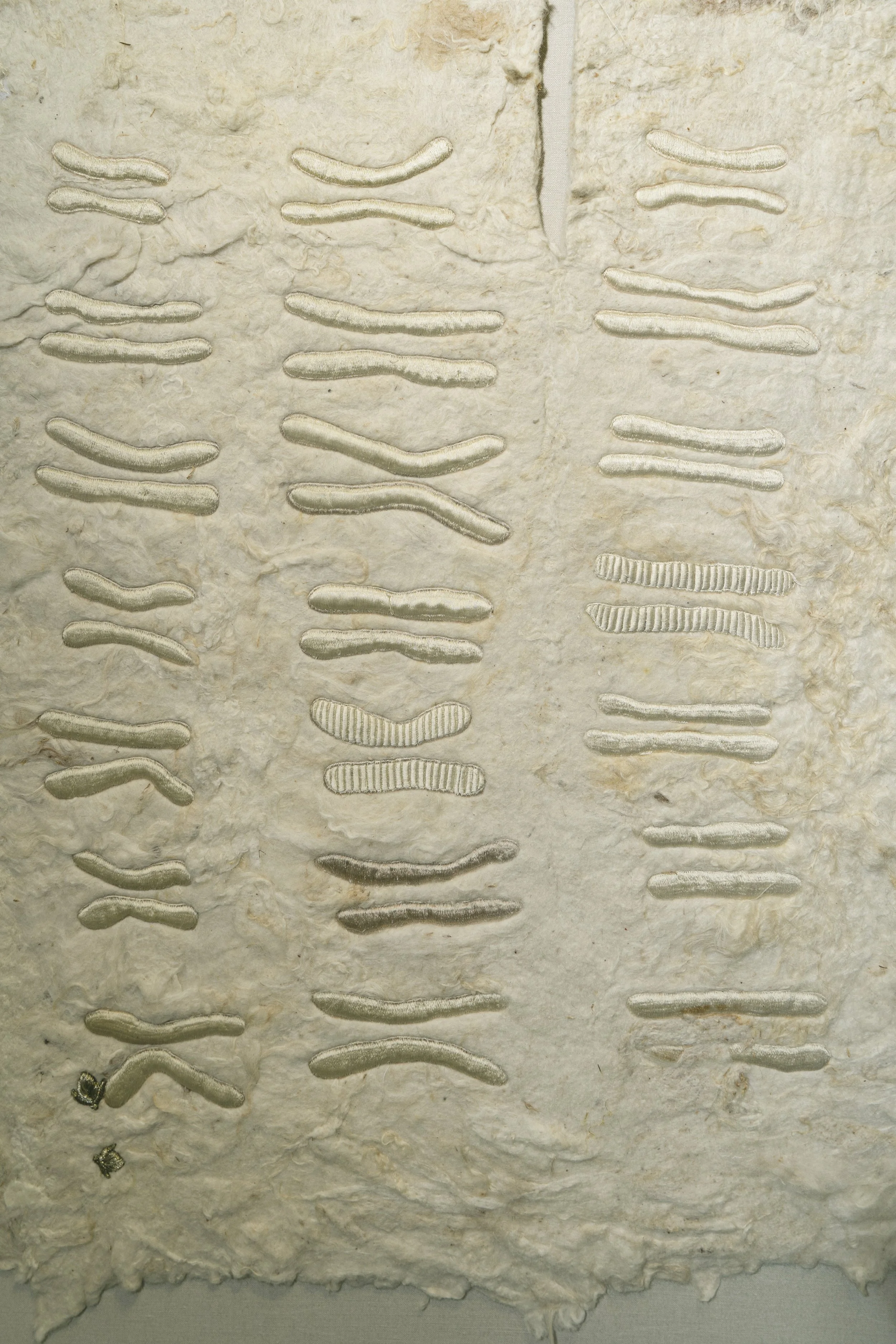

Cosmic Digressions, Embroidered Felt Dyed in Iron, 2020.

Aegilops Tauschii, Embroidered Felt, 2020.

Braided Sheep Skin.

Shepherd’s Cloak, Braided Sheep Skin, 2020.

LŠ: The Utility of Being assembles pelts—by treating and collecting the skins, what did you learn of the material itself? And of the journey of the animals?

AP: Viewers were invited to navigate the space as a domestic animal might, guided by a walking tour developed with Cave Bureau, with whom I was exhibiting. This shift in orientation, moving as the animal, created an embodied empathy.The journey of the animal began to mirror one’s own.

The pelt carries the animal’s last image, its surface memory. Porous, scarred, fragrant.

As the skin is washed, treated, preserved, deodorized, it begins to exit its former life. It becomes material. It becomes an object. But it never fully leaves the animal behind. Working with it means holding that tension between presence and absence, utility and identity.

LŠ: How do the felts speak to the fragility of existence?

AP: Felting is a process of abrasion and cohesion. It mimics life in that sense. Loose fibers bond through friction and heat, much like relationships, systems, and bodies. The work oscillates between form and collapse.

Aegilops Tauschii, Embroidered Felt, 2020.

Entangled Matters, Karyotype 1, Embroidered Felt, 2020. All images courtesy Adrian Pepe.

LŠ: What are some of your upcoming projects? Are you exploring any new materials or techniques?

AP: I’m working on a new project that explores gestures of making as performance. I'm returning to early processes like spinning and weaving, but through the lens of choreography. I’m also interested in the interface between craft and movement, between labor and stage. Performance is becoming a space for my material to speak differently. Beyond object, beyond utility.