KUNLÉ ADEYEMI

Kunlé Adeyemi, courtesy NLÉ.

Kunlé Adeyemi is an architect, professor, and development strategist whose works are internationally recognised for originality and innovation. He is the founder and principal of NLÉ – an architecture, design, and urbanism practice founded in 2010, for innovating cities and communities.

Adeyemi’s notable works include ‘Makoko Floating System (MFSTM)’ - a groundbreaking, prefabricated, building solution for developments on water - deployed in 5 countries across 3 continents, with the latest iteration Mansa Floating Hub in Sao Vicente, Cape Verde. This acclaimed project is part of NLÉ’s extensive body of work and new venture - Water Cities® Group and the African Water Cities Centre – focused on the intersections of rapid urbanisation and climate change.

Other projects include A Prelude to The Shed in New York, USA, the Black Rhino Academy in Karatu, Tanzania, and theSerpentine Summer House at the Royal Kensington Gardens in London, UK. Alongside his professional practice with multiple prestigious awards, Adeyemi is an international speaker and thought leader.

He is one of UNDP’s Africa in Development Supergroup members. Adeyemi was an Adjunct Visiting Professor at the University of Lagos, following appointments in various institutions including Harvard, Princeton, Cornell, and Columbia Universities, where he leads academic research in architecture and urban solutions that are closer to societal, environmental, and economic needs.

LUCIJA ŠUTEJ: NLÉ was founded in 2010 following your time at the OMA. Could we speak of the origin of the name and the ethos that guides the studio?

KUNLÉ ADEYEMI: NLÉ means ‘at home’ in Yoruba, the language of Africa’s first truly urbanized population. From the 11th century onwards, the Yoruba lived in a network of West African cities characterized by sophisticated commercial and governing structures. But within NLÉ’s philosophy, the home is much more than walls, floors, and ceilings. Instead, it refers to the fundamental building blocks of the city, to everyday life, and the uses of public space in the emerging and endlessly complex urbanisms of developing regions.

LŠ: Your research into floating cities and their evolution was first presented as a prototype through the work Makoko Floating School (2012) - initially a self-funded prototype. How did the local community, techniques, and landscape inform the design?

KA: It started with trying to address the challenges of affordable housing with state governments. And through it, we realized the implications and the impact of climate as a result of a flooding incident. And that became this project that we call the African Water Cities, which is a study of intersections of climate impacts and urbanization. The construction was supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), under the Africa Adaptation Programme. The project was always about climate adaptation. It is a prototype of one building out of many that would be a part of the African Water Cities climate adaptation ecosystem.

The local community has built thousands of homes on stilts, where the source of inspiration was taken from a timber lightweight structure. Our first task was to understand the environment and learn from the community— how they do and could build. It’s so much with so little, looking at the limitations and challenges that they had.

MFS I – Makoko Floating School, Lagos, Nigeria, 2011.

MFS I, Lagos, 2011.

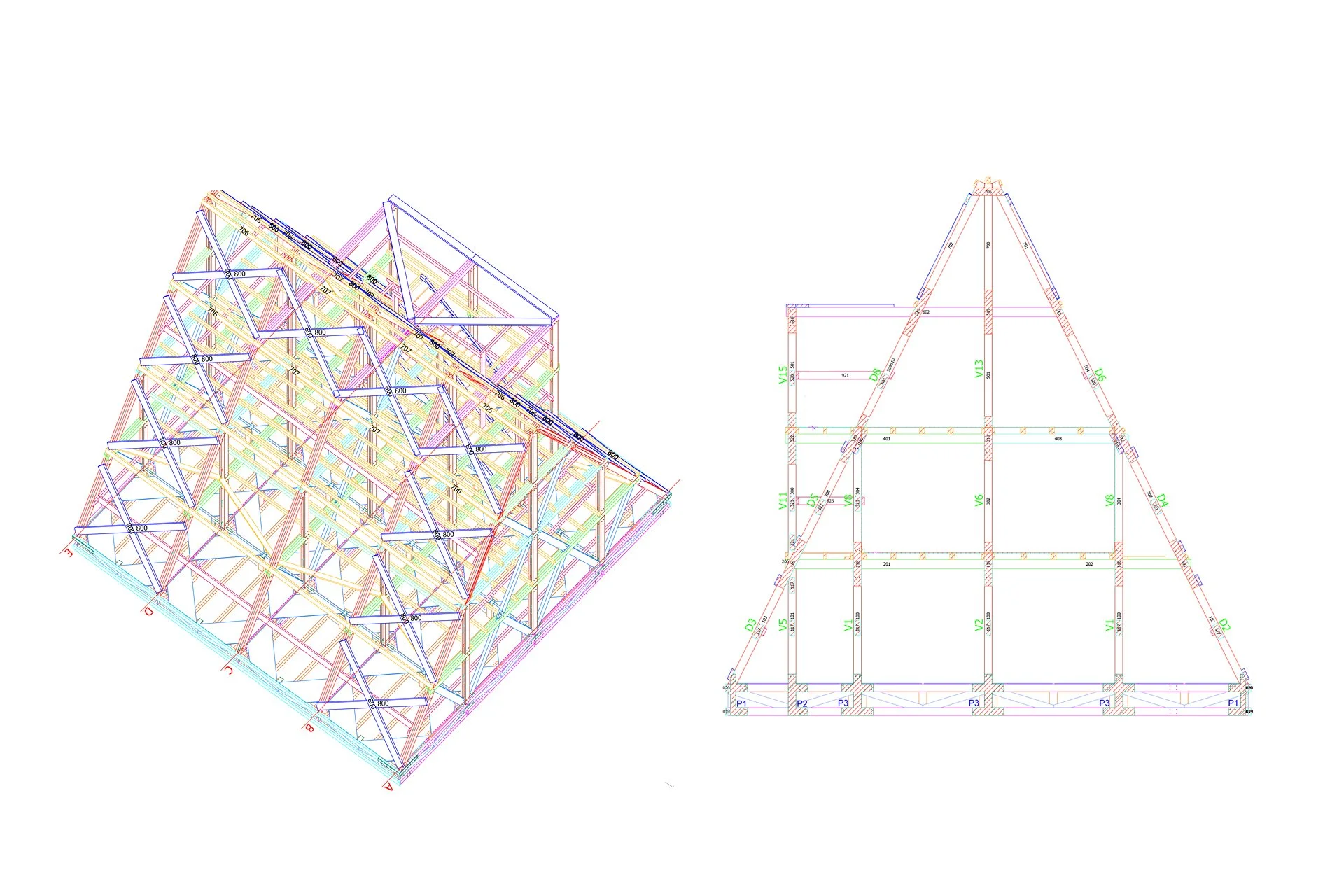

MFS™, 2011-.

MFS™, 2011-. Images by NLÉ.

LŠ: The design of the school evolved into the concept of MFS™, which has since seen many editions and further development, such as the presentation in 2016, Venice Biennial (awarded with Silver Lion), and more recently, Cape Verde’s Floating Music Hub. How did each location’s geography, cultural, and community needs shape the design?

What materials evolved over the editions?

KA: MFS has always been a prototype for a building system that is meant to be modular, scalable, and adaptable to various environments. The idea is to create a specific structural system, which is easy to fabricate within a local context, easy to assemble, and even disassemble. The first edition, which we built in the community, was inspired by them and to test the idea.

In Venice, we added additional engineering with better connections, scaling up, and modularity. We are constantly improving the engineering to build a simpler structure with fewer elements within the system. To date, we have scaled across various types of wood and worked with local materials.

MFS II, Venice, Italy, 2016. Courtesy: Images by NLÉ

MFS II, Venice, 2016. Image by NLÉ.

In China, specifically Chengdu, we worked with bamboo due to its abundance in the area. While the Cape Verde’s Floating Music Hub was built in the ocean, which required specifications to reduce corrosion. While we engineer each edition to a specific region, materials also inform the design, while the structure is always a timber frame.

Each iteration to date has enabled us to develop and implement new ideas to improve on the previous one. With the modular approach, we can also demonstrate the possibility of assembly, disassembly, and even storage of a building. Each challenge was for us a way to acquire new knowledge on how to create a modular, scalable model.

MFS IIIx3-Minjiang Floating System, Chengdu, China, 2018. Image by NLÉ.

MFS IIIx3, Chengdu, 2018. Image by NLÉ.

LŠ: Which specific locations do you see as potential sites for the next editions of MFS? How can we adapt the system to different locations?

KA: We are working on redeveloping Makoko, a community where we started, with a wider range of typologies. Drawing our inspiration from the local inhabitants, we were inspired to regenerate the area into a water-based settlement, from floating structures to steel housing. Presently, we have about 8-10 building solutions to regenerate what might be one of the first purpose-built water-based settlements in Africa.

MFS III - Minne Floating School, Bruges, Belgium, 2018. Image by NLÉ.

MFS III, Bruges, 2018. Image by NLÉ.

LŠ: The African Water Cities rethinks urbanization and emerged from your research on affordable housing. It identifies water scrapers over skyscrapers. What did you see as the most pressing issues, aka knowledge gaps, in terms of urbanisation and adaptation?

KA: I think the fact that was most pressing to us is that nearly 80% of cities and capitals around the world are by a waterfront. Unless you look at these numbers, you do not see the scale. A lot of these places are affected by the impact of climate change. We have a situation where there's urbanization, people trying to move towards cities, and concurrently, there are threats from the environment. We could say there is a point of convergence, almost a collision of forces, happening at several of these cities, and particularly on the African continent. Nearly 70% of these cities are by waterfronts, whether it's a river, a lake, a lagoon, or an ocean. There's a lot more vulnerability.

Asia is also significantly affected by this challenge; however, Asian cities are adapting and mitigating these conditions already, building cities and communities on water. On the African continent, where there's a huge growth, the infrastructure and planning for what is seemingly inevitable are lacking.

African Water Cities by Kunlé Adeyemi, 2023.

Images by NLÉ.

LŠ: You mentioned cities across Asia are adapting to new conditions very well. Do specific examples stand out?

KA: Many, specifically in Vietnam and in the Philippines. They are homes to many communities that have and are building on water. I am also thinking of Cambodia, where there is a growth in population and urbanisation, with adaptation to building on water as a solution.

LŠ: What do you see as imminent challenges - policy or technical?

KA: I think both. Many cities do not have a policy for building on water or the technology that is adaptable for that environment. When you talk about Asian and African cities, there are certain peculiarities in materials and cost. There is a need for solutions that are affordable.

Affordability is key to this process of building. To find solutions that are sustainable in the long term. So, developing a project technically is important; however, making it economically viable is very important. On our project for example, we have some support from UN Dap and UN-Habitat on the feasibility studies and project preparation.

LŠ: What is next for MFS? Are you currently working on new prototypes?

KA: We are looking to develop a neighbourhood that demonstrates not only architectural solutions but also the supporting infrastructure, from water, sanitation, to waste management. We want to test how we can develop a sustainable and viable community on water that addresses the environmental issues, but is also accessible to a wider range of inhabitants.

As in the case of Makoko, we want to preserve the quality of life of a community. So, that is currently our biggest challenge, and we are in the process of raising funds to develop this pilot and to make sure it is financially viable and attractive for investments. Through our 14 years, we have acquired a lot of knowledge— from prototyping, we have seen where it works, where it fails, and the misconceptions. That's what you do with innovation - test and trial. Each time, there is a chance to improve on technology.

LŠ: For a final question, how do you see the challenges and opportunities of the future of the architectural field? What do you think we should prioritize moving forward?

KA: That is a big question! (laugh)

LŠ: Ones we like. (laugh)

KA: Well, we can only speak for ourselves. (laughs) I think there are lots of priorities out there. The emerging technologies allow us to automate the mundane tasks and enable us to focus on even more specific things. I think the core value is continuing to find ways to promote and bridge diversity and coexistence between humanity and the environment. I think that is the key.