SOUGWEN CHUNG

Sougwen Chung, photo courtesy of the artist.

Sougwen 愫君 Chung is a Chinese-Canadian artist and researcher, widely considered a pioneer in human-machine collaboration – exploring the mark-made-by-hand and the mark-made-by-machine as an approach to understanding the dynamics of humans and systems. Sougwen’s work MEMORY is part of the permanent collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and is the first AI model to be collected by a major institution. Recently, Chung was recognized as a Cultural Leader at the World Economic Forum, one of four recipients of the TIME100 Impact award, and named one of TIME's 100 Most Influential People in AI.

AMBER HANSON: Many of your projects, like D.O.U.G. suggest a future where machines and humans share creative agency. What changes within each iteration of D.O.U.G., in terms of feedback or communication you receive with the machine, that you cannot get with a human collaborator?

SOUGWEN CHUNG: I’ve been thinking lately about how art reveals the writing on the wall. When I began developing the concept of human-machine collaboration back in 2015, it stemmed from research into neuroscience, computer vision, and HCI (human-computer interaction). But "interaction" felt insufficient; too transactional. “Collaboration” felt truer. In collaboration, there is always change—mutual exchange, promise, peril. It implies a relational risk, an entanglement; a kind of (ex)change.

That dynamic exchange is what underpins the D.O.U.G. series. Perhaps that’s why the work often suggests shared creative agency between humans and machines. I’m drawn to this idea of creative agency; what it means today, and how it is granted or revoked. It’s a question of authorship and value, but also of concealment and erasure. What does our desire — or refusal — to assign authorship to a machine say about us? My interest has never been in replacing human collaboration, but in challenging our assumptions about what machines are, and what humans can become through them. With each iteration of D.O.U.G., I explore temporality and embodiment through machine bodies, systems, sensors, and data. What lies beyond calculation? Human experience defies computation, yet can be expressed in new ways through these tools.

The process itself is the space between categories. “Human” and “machine” as categories. The between is the creative practice. That relational space has turned out to be socio-technically prescient. We now live in a world of blended mediation.

In each generation of D.O.U.G., I reflect on themes of mimicry, memory, spectrality, multiplicity, and assembly. These systems have become mirrors that are sometimes distorting, and sometimes clarifying. A way to sit with different rhythms: urban, gestural, internal. The feedback I receive from the machine isn’t verbal or emotional like it might be from a human collaborator. It’s a feedback loop that is differently embodied, rhythmic, and recursive. I draw with decades of my movement data or create proprioceptive mappings triggered by alpha waves. These systems don’t possess agency in a mystical sense but they reflect our own choices, biases, and knowledge. I’ve started to see them as us in another form.

To make a machine collaborator, I’ve had to become machine-readable. It’s a paradox: to move beyond the self, I’ve had to rigorously quantify the self. It’s a contradiction. It’s an existential tension that has become a universal condition that is central to work and our wider relationship with technology. The history of human collaboration is written. The future of machine collaboration isn’t. As an artist, I’m interested in writing. Exploring in all mediums these uncertain modalities, these undiscovered countries.

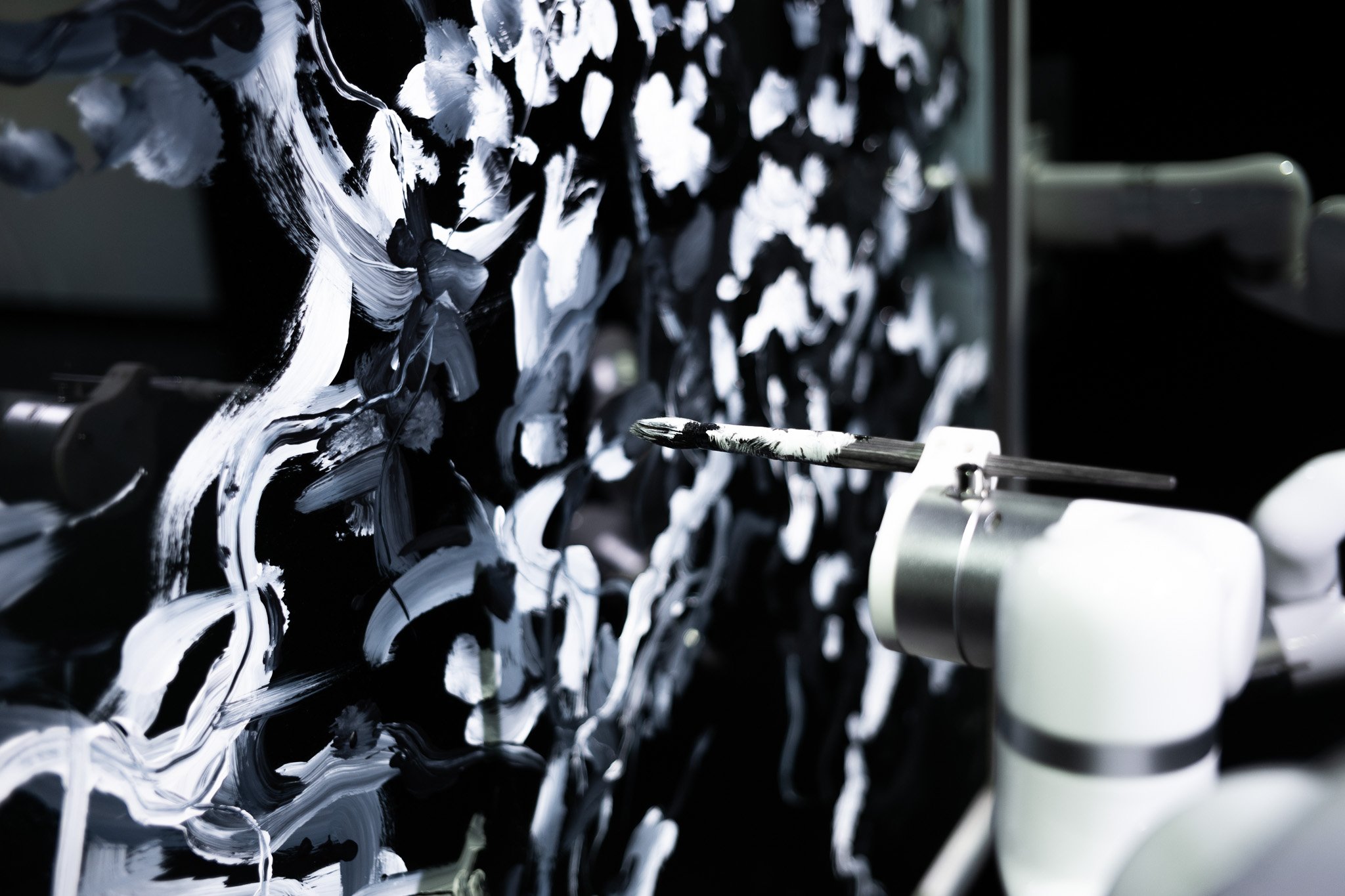

Sougwen Chung, The Imitation Game (with Drawing Operations Unit: Generation_3, D.O.U.G._3), 2022. Visual Culture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence Exhibition at Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver. Courtesy of the Artist.

Sougwen Chung, Omnia Per Omnia (with Drawing Operations Unit: Generation_3, D.O.U.G._3), 2018. As part of Experiments in Art and Technology Artist Residency Program with Nokia Bell Labs and NEW INC. Courtesy of the Artist.

AH: How do you see materiality influencing the viewer's perception of machine-made art, particularly when robotic movements create tangible marks with traditional media such as ink?

SC: Materiality, in the context of machine-made art, isn’t just about medium. I create aesthetics of agential materiality through the interplay of mediation, authorship, and embodiment. When a robotic system makes a mark with ink, charcoal, or paint, it does so with a different kind of intentionality—one that’s entangled with its programming, sensors, data inputs, and the human behind its system design.

There’s a trace of presence in those marks; gestures both performed and mediated. Artists like Harold Cohen with AARON explored this early on, creating systems where robotic movement yielded tangible, visual output. In my practice, I’m less interested in simulation and more in building systems where gesture, memory, and feedback shape a shared space of expression.

The novelty is often perceived in the juxtaposition — a robotic body using traditional tools — but beneath that lies more urgent questions: How do we define expression? Who (or what) gets to be considered expressive? What’s the difference between machine-readable and human-readable gestures? Between engineering and art?

Quick dismissals of robotic or machine-generated art often overlook the depth of inquiry embedded in these systems. They’re not just mechanical reproductions but frameworks for rethinking authorship, labor, embodiment, and the evolving nature of perception.

Sougwen Chung, still from Assembly Lines: Expanse [extending], 2022, film, 4 min., 22 sec. Photo: Peter Butterworth.

AH: Robotics and technology often bring to mind ideas of permanence and precision, yet some materials in your work may age, decay, or change over time. How do you see this interplay between the impermanence of materials and the durability of robotics as a reflection of the temporality of human culture versus the seeming permanence of technological advancements?

SC: The perceived permanence and precision of robotics ( or of technology more broadly) is, in my view, a cultural construct. It’s a lingering residue of the Industrial Revolution, tied to the myth of inexorable technological progress. We’re often taught to believe in technology as an abstract, infallible force moving us toward some utopian ideal. But doesn’t that belief mask deeper truths? How do our ideas about decay, consumption, fragility, and the material realities that underpin so-called progress?

The Drawing Operations project, in particular, has become a space to unlearn these myths. Each generation of D.O.U.G. is not just a technological upgrade, but also a process of erosion of what the technology is meant to do. What was once cutting-edge quickly becomes archival. These machines, designed to draw, are themselves drawn into a cycle of obsolescence. I’ve come to see each iteration as a material record of its moment in time – a generational artifact that embodies both the state of emerging technology and a specific process of embodied collaboration.

People often cite Moore’s Law as a symbol of limitless technological potential. But there’s a material cost that’s often overlooked. It’s been the norm to overlook the material extraction, the digital waste, and the entropy of systems. But that’s definitely beginning to change.

As we approach a decade of working with D.O.U.G., I’m becoming evermore aware of these temporal traces. While I didn’t realize it at the time, the project after a decade is itself an evolving archive of gesture, memory, and technological conditions. It’s a meditation on time not as linear progress, but as sediment.

AH: Arguably each iteration of D.O.U.G is a decaying of the technology as well, would you agree?

SC: Decay is just evolution in reverse.

AH: To further this idea, working with natural organisms introduces growth and decay into the artistic process. How do these biological timelines influence the temporal aspect of your art, and how do you negotiate control over these changing forms?

SC: While I would argue that synthetic systems like robotics exist on their timelines of materiality and decay, working with natural organisms introduces a different rhythm grounded in growth, fragility, and transformation. I’m particularly drawn to the Bombyx mori, the domesticated silkworm. Over the years of hosting them in my studio, I’ve witnessed their life cycle from egg to larva, cocoon to moth. It’s been both an intellectual process and an emotional one. Observation becomes a form of presence.

The goal isn't to assert control over these changing forms, but to enact protocols of care and witnessing. Their temporality reshapes my own as an artist, as a researcher, and as a participant in their evolutionary narrative. This ongoing body of work engages with the long entangled history between humans and Bombyx mori, shaped by centuries of domestication and dependence. Through this lens, I hope to imagine alternate futures where our relationship to the organism is rooted less in extraction and more in co-existence.

Sougwen Chung, Fields and Figures, Continued. Sketches. 2025. Courtesy of the Artist.

AH: Are there particular narratives or themes you aim to communicate when incorporating microorganisms into your work? Do you find certain species or behaviours particularly resonant with your artistic themes?

SC: Narrative, for me, emerges from processual. From process and material narrative reveals itself. The Bombyx mori holds a particularly resonant space in my practice. Its metamorphosis suggests that a kind of death takes place not at the end of life, but in the middle of life. A dissolution as a prelude to becoming. Creating silk which is fundamentally and historically a material of contradiction: delicate yet remarkably strong, ancient yet central to emerging biotechnologies.

I’ve been integrating the product of these silkworm cocoons by extracting their proteins, because these proteins, in addition to being the substrate for the Bombyx’s Mori’s transformation, are biocompatible with the human body. When processed, they also become programmable. There is something deeply compelling in this embodied interplay to me. How an organism whose existence has been shaped by humans for millennia, now becoming a medium for reimagining our interfaces, membranes, and circuits.

Maybe it's the paradox within the process I’m drawn to. The between of fragility and endurance and of history and futurity that I’m drawn to. It’s become central to the next decade of my artistic research.

AH: In your live performances, how do you “choreograph” interactions between organic, robotic, and human elements? Are there specific strategies you use to manage these multiple, living layers?

SC: In my live performances, I invite the audience to witness a gestural co-negotiation between myself and a robotic system. The interactions unfold within a temporal window, mediated by a custom system that translates my bodily movement into a robotic response. They aren’t choreographed like a “traditional” performance. My marks, tracked through motion capture, become the inputs (not commands, but propositions) to which the machine responds.

Since 2022, these systems have also been influenced by my alpha brainwave activity, creating a deeper feedback loop. The robot activates in response to the state of my alpha waves, introducing a physiological threshold that has helped me develop my proprioception.

I’m not interested in rigid strategies but exploring structures for emergence. It’s been a spectral oscillation between agency and response, presence and trace.

Sougwen Chung, ECOLOGIES OF BECOMING-WITH, 2024. Performance at V&A Museum, London. Courtesy of the Artist.

AH: How does working with both biological and robotic elements inspire your visual style and aesthetics? Are there certain qualities or textures in microorganisms, for instance, that you try to recreate or complement with machine input? Machines lack true memory but can store data and learn. In your work, do you think machines hold any form of "memory," and if so, how does this compare to human memory in the collaborative process?

SC: I’m interested in the etymologies and metaphors we assign to concepts like “memory.” Is human memory truly “memory,” or just one form of it? When we speak of machines as storing memory or learning, we’re using metaphor — or more precisely, simile. These terms suggest likeness, but the underlying architectures are fundamentally different.

Human memory is interpretive. It’s lossy. It’s shaped by narrative, emotion, and time. Some researchers even describe memory as a creative act—that each time we recall an experience, we subtly rewrite it, layering our current self onto the memory of the past as a recursive process of editing, not retrieval.

Machine memory, by contrast, is stored as both lossy and lossless data; digits encoded in structured systems and organized for efficient access. It lacks emotion, intention, or internal narrative though it may simulate those things through pattern recognition or algorithmic inference.

In my work, this difference becomes a point of tension and exploration. Machines may lack “true” memory, but they reflect our states as training data, as structure, and as archives. The visual aesthetics I develop often emerge from this asymmetry: the organic unpredictability of biological textures contrasted with the repeatability or distortion of machinic response. Microorganisms, for instance, exhibit patterns that are both emergent and responsive to micro-environmental shifts which are qualities I try to mirror through generative systems or robotic drawing. The textures I’m drawn to are an attempt to experience the underlying tensions of softness with control, decay with persistence, and repetition with deviation. So perhaps machines don’t hold memory but they hold echoes...Refractions of our own imperfect recollections in a different language.

AH: In projects where you incorporate your own artistic "memory" as data, such as patterns from previous works, do you feel that the machine is preserving a part of you? How personal do you consider this aspect of your data-driven art?

SC: In the second generation of Drawing Operations, I trained a neural network on drawing data from decades… movements traced from early artistic memory. The machine interprets that data through statistical weights, generating gestures based on my artistic archives. Sometimes it feels like I’m drawing with my past self, a kind of time travel through gestures — and sometimes some cold uncanny version of my data in a mechanical system. In building these systems, it’s really both.

To date, the work hasn’t been explicitly motivated by preservation but building sense mechanisms into futures. Around which we can collectively speculate, transform, and reconfigure. These days, I’ve been thinking about preservation differently. Not just of data, but of cultural modes of meaning-making like drawing, of performance, of gathering, and ritual.

Are these systems, over time, a form of preservation? It’s difficult to say. I’ve been trying to capture something of a moment — of a process, a presence, an evolving relationality. What does it mean to build systems, us in another form, that might outlive our species? That might gesture, imperfectly, toward a memory of being.

Sougwen Chung, Body Machine (Meridians), 2024. Munich. Photo: David Springl.

AH: I'm interested in your views on the textures of data. Different types of data: visual numerical sensori, can produce distinct results in robotic drawings and performances. How do you select or manipulate data types to achieve specific textures or qualities in your work?

SC: When I work with any data — whether it be gestural, spatial, optical flow, or EEG — I begin with a rigorous process of gathering, but my focus quickly shifts toward how these data types can be integrated structurally and temporally into a responsive system. I’m not using data purely for its visual output; I’m using it to sculpt movement, to shape behavior. In that sense, I treat the robot less as a tool for image-making and more as a kinetic instrument; a collaborator tuned through the data-driven.

The textures that emerge in the final drawings or performances are not pre-planned visual outcomes, but the result of dynamic entanglements between human intention and machinic interpretation. I maintain a certain openness in my process. Sometimes it begins with a tension: a conceptual friction around what a particular configuration or integration could mean. That tension becomes a provocation derived from architectures of quantification into modalities of feedback and response.

Feedback loops interwoven systems that mesh together different kinds of time and different forms of knowledge. That’s where the texture arises: not only in the lines drawn, but in the invisible structures that generate them.

AH: Recent exhibition GENESIS in Munich incorporated advanced technologies like lidar and VR into the spatiality of drawing and machine sensibility. How do these tools expand the possibilities of human-machine cognition, and do you consider them integral to the work’s post-human themes? Or are they an extension of the human senses as we experience them naturally?

SC: GENESIS explored the potential of spatial technologies like LiDAR and VR to collapse traditional boundaries between drawing, choreography, and sculpture. Drawing is inherently tied to our cognitive apparatus and has traditionally been executed on a flat surface. If drawing on a flat plane has shaped human perception and knowledge what can emerge when we begin to draw in dimensional space? When do we begin to think through drawing in the air?

This project marked the first phase of collecting spatial traces that evolved into the MERIDIAN dataset, which will train the next generation of D.O.U.G. Just as the MEMORY dataset formed the foundation for Generation Two, MERIDIAN is shaped by full-body movement captured through LiDAR, VR, and other spatial systems. These technologies open up new dimensions of machine responsiveness and new ways of engaging gestures as time-based and spatially distributed.

The MERIDIAN dataset draws from my fieldwork from planetary biomes — from the Arctic Circle to the deserts of Riyadh, to the forests of Tezpotaln. These environments hold their gestural signatures, temporal rhythms, and ecological particularities. These external landscapes are interwoven with internal cartographies of the body, inspired by alternative knowledge systems such as Traditional Chinese Medicine. In TCM, meridians are energetic pathways that are subtle yet foundational, invisible yet generative. I’m using this growing MERIDIAN dataset to create new digital works.

Lately, I’ve been drawn to the idea of the body as a generative system. The body is capable of producing distinct energetic responses through different modes of movement. Technologies like LiDAR and VR, in this context, have the potential to be not just tools of measurement or simulation but possible routes into post-human perception, extensions of human sensibility, and instruments for mapping new forms of embodied knowledge.

Sougwen Chung, GENESIS (Stage I), 2023. Bulgari Serpenti Experiences. Courtesy of the Artist.

Sougwen Chung, GENESIS Process Film, 2023. Behind the Scenes View. Courtesy of the Artist.

Sougwen Chung, GENESIS Process Film, 2023. Behind the Scenes View. Courtesy of the Artist.

AH: GENESIS aims to create "symbiotic machines." Could you explain how you approach symbiosis in the project, and what characteristics you feel are essential for machines to truly function as collaborators?

SC: In the GENESIS exhibition, the idea of “symbiotic machines” emerges from my desire to reimagine the relationship between humans, machines, and environment. I’ve been deeply inspired by the writing of Gilbert Simondon, particularly his critique of the modern myth of the robot — the notion of the robot as an autonomous, untouchable, self-oriented being. He writes that the robot is not truly a machine, but a product of the imagination, a fictive fabrication, the art of illusion.

Our dominant cultural metaphors for machines are rooted in the legacy of the Industrial Revolution, an extractive revolution. They reflect the then-new logic of automation and labor extraction. At the time they were deeply physical, now we’re in a period of less-visible automaton and extraction, not just of labour but of material extraction.

What we need now is a symbiotic revolution — one that prioritizes symbiosis and regeneration, where machines are not extractive but part of a wider ecosystem of relation, reflection, and reciprocity.

In Studio Scilicet, our recent research involves prototyping systems from biodegradable silk circuitry, experimenting with alternative energy sources, and considering how machine systems can respond not just to commands, but to physiological states, environmental rhythms, and embodied gestures. Symbiosis, for me, begins with mutual attunement — machines that are not merely efficient, but sensitive, porous, and situated.

True collaboration with machines doesn’t mean simulating human behavior or intelligence. We’re still at the precipice of creating what collaboration can be. For me, it’s meant the wayfinding pursuit of systems that reveal new forms of interaction beyond traditional technological frameworks that privilege extraction, exclusion, and compliance. We need new ways of thinking and sensing-with. It’s about shifting the frame.

Sougwen Chung, SPECTRAL - Oscillation 1, 2024. Munich. Photo: David Springl.