YUMA YANAGISAWA

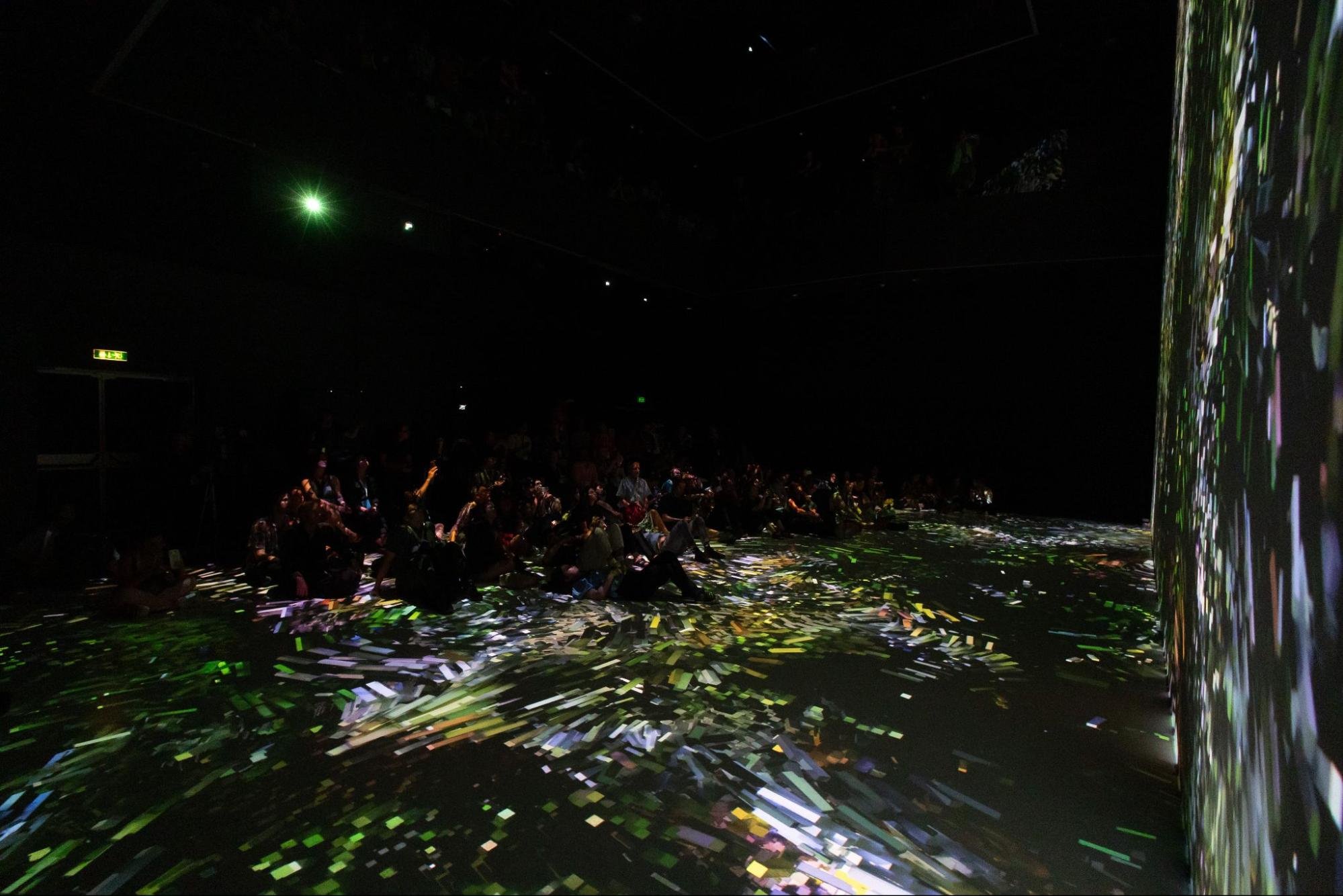

Photo: Sarah Annovi Stuart

Yuma Yanagisawa is a Japanese media artist based in Berlin whose practice explores real-time generative systems, immersive installations, and the intersection of nature, time-based systems, and perception. His work focuses on the poetic potential of computation, creating ephemeral environments shaped by algorithmic processes.

His works have been presented internationally at Ars Electronica, MUTEK Tokyo, and NODE20 at Mousonturm (Frankfurt), and have been licensed for long-term exhibition by CODE – Centre of Digital Experiences (Veszprém, Hungary). Yanagisawa has also created commissioned projects for Shiseido, Nikon, and Cartier.

AMBER HANSON: What kind of people do you find most interesting to watch engaging with your work? Are there particular reactions or ways of interacting that stay with you?

YUMA YANAGISAWA: I find it interesting when people take a photo or video of the work. In an exhibition setting, even if the piece is a fixed sequence, the nature of the simulation is ephemeral, each moment is constantly flowing and decaying. I think the audience instinctively wants to archive these moments because they feel fleeting. Although the work isn't 'interactive' via touch, that act of trying to capture the image before it dissolves is a form of deep interaction.

AH: Your works often feel immersive yet calm. How consciously do you design the atmosphere of an experience (light, rhythm, timing) to guide how people feel in the space?

YY: I am very conscious of it. I view it like a chef cooking a dish. A chef decides the ingredients, their exact proportions, and the precise moment to add each element based on their subjective taste, but one that is grounded in years of tasting and cooking. Similarly, I use rigid parameters to engineer a specific atmosphere. The system is logical, but the final flavor of the experience is emotional.

AH: Some of your materials, whether GPU rendering, data feeds or older technologies, carry their own histories. How conscious are you of those histories when you use them?

YY: I think it depends on the technology. Learning history helps you understand it better, but I don't think it's always necessary. Art school students learn art history, but only a tiny fraction of them become full-time artists. This is because I think they end up merely scratching the surface without locating their practice within a historical context.

I'm fairly clear about the technological topics I've been working on for years, such as real-time rendering. What I like about particle simulation is that it basically only improves as time passes, thanks to newer graphics cards, drivers, and so on.

AH: Your installations often reveal the workings of their own systems. Is that transparency something you build in deliberately, or does it emerge naturally through the process?

YY: My practice is hands-on; I want to be clear about who did what rather than obscuring the authorship as co-creation. Since I am the primary or sole author of each project, I naturally share works in progress. My projects also tend to be multi-layered, and I enjoy exploring each layer separately, which often results in revealing the underlying structures of my systems.

Fluid Dynamics, Yuma Yanagisawa (2025)

AH: When you begin a new piece, how do you decide which algorithmic system or structure to work with, and what tends to draw you to a particular logic or process? Is there a go-to that you have?

YY: Media art is closely linked to current technological trends, so I tend to consider how they can be integrated into my existing practice. For me, maintaining the aesthetically coherent quality of my practice is important, so I tend to choose algorithms, structures, or tools that support that goal.

AH: How much do the conditions of display, the projection scale, hardware limits, or spatial setup influence the final form of your work? Or is the site of the artwork a secondary consideration?

YY: I'd say it's important, but what you project is more important. Historically, media art is much more tied to systems design than architectural design. For me, scaling up is a way to make my work exhibition-ready. Generally, I aim for large-scale installations, but that doesn't mean my work cannot be exhibited on a typical display or speaker.

In other words, I don't think about the canvas size of a project first. Rather, I decide what to draw in the project and then the scale will follow, given realistically available technical infrastructure.

AI Flowers / Yuma Yanagisawa (JP), Photo: Markus Schneeberger (2023)

AH: Generative systems often sit between control and unpredictability. How do you navigate that balance when you're composing a piece in real time? Does working with natural forms provide this balance before you begin?

YY: I lean more towards control. The balance is very important because it shows the intent of the creator. I think the beauty of generative systems is discovered when the author builds a system that depicts a sort of 'ordered chaos,' and I believe the artist should tame the system to reveal it.

Nature provides the clearest references for this. Ocean waves, for example, are one of the best demonstrations of beauty in chaos—they are wild and unpredictable, yet strictly governed by physics.

AH: Do you think of your systems as more like musical scores, electronic circuits, or living organisms? Alternatively, is there an analogy to help us understand your own perception of your practice?

YY: Yes, I've recently developed a conceptual framework to describe my practice. My practice is grounded in the concept of Computational Ephemerality.

Computational Ephemerality is not an invention of new technology, but a shift in the observer's focal point.

In an era where generative AI promises infinite production and perfect loops, our eyes are trained to see the "flow" - the continuous stream that moves ceaselessly. My practice quietly reorients this gaze from the immortal system to the individual particle.

By zooming in on the microscopic lifecycle of these instances, we discover that what appears to be a fluid macro-structure is actually a sequence of incessant dyings. The system may persist, but individual existence within it vanishes.

This work imbues the machine with the poetic reality of Hakanasa - the appreciation of fleeting existence. By engineering specific ends for these entities, I propose a new form of digital naturalism: one where existence acquires value precisely because it eventually ends.

Installation views, courtesy of the artist.

AH: Generative works can be fragile or dependent on specific systems. What do you think about the lifespan of a piece once the software or hardware it relies on becomes obsolete?

YY: This question is well connected to Computational Ephemerality. I think the life of a piece, as a runnable system, ends once the software or hardware becomes obsolete. However, as far as I know, institutions like ZKM have specialists who work to handle this problem. So you may be able to experience it in such a specialised institution.

AH: You move easily between visual art, design, and technology. Has working with commercial or performance contexts changed how you think about what an artwork can do?

YY: Media art is inter- or multi-disciplinary by nature, and the influence from the commercial world and festivals like MUTEK cannot be ignored. It's crystal clear once you have a look at the history, even briefly. However, I've met countless people who claim that art is not design, that anything beautiful is mere decoration, and who only accept sine waves and black-and-white glitches that we saw twenty years ago. They fundamentally misunderstand what this art form can do, in my opinion. Trying to be another John Maeda in 2026 is a disciplined and beautiful attempt. But after we saw media art aesthetics go mainstream, I’d like to reach the general public—not the nostalgia-driven gatekeepers.