STEFANO BOERI

Stefano Boeri, photo by Laila Pozzo ©Michelangelo Foundation

Stefano Boeri (Milan, 1956), architect and urban planner, is a Full Professor of Urban Planning at the Politecnico di Milano and Director of the Future City Lab at Tongji University in Shanghai.

Architect of the Bosco Verticale (Milan, 2014), Stefano Boeri’s work ranges from urban visions to design, with a constant focus on the geopolitical and environmental implications of urban phenomena. As President of Triennale Milano (since 2018), he is Commissioner of the 24th International Exhibition “Inequalities” (May–November 2025).

He is President of the Fondazione Futuro delle Città and of the Scientific Committee of Forestami, the urban forestation project in the Milan metropolitan area.

Leading figure in the climate change debate in international architecture, Stefano Boeri is also known for his research on urban forestry and biodiversity implementation and is co-president and member of the scientific committee of the World Forum on Urban Forests (Mantua, 2018; Washington, D.C., 2023). In 2023, he was also awarded an honorary degree in Chemical, Geological, and Environmental Sciences by the University of Milano-Bicocca; and in the same year, his Green Obsession design approach received the UN SDG Action Award in the “Inspire”; category for supporting the implementation of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals.

In addition to his design work, Stefano Boeri is known for his research, visions, and master plans for the future of urban conditions around the world. He has been involved in designing regeneration and development plans for metropolises and large cities, including São Paulo, Geneva, Tirana, Cancun, Riyadh, Cairo, and, in Italy, Milan, Genoa, Cagliari, Naples, Padua, Taranto, and many others. From 2022 to 2025, he directed the Laboratorio Roma050, which aims to propose a new urban and territorial vision for Rome.

His research has been published in international books and journals; his books include: Il territorio che cambia (Milano 1992); AAVV, Mutations (Barcelona 2001); Multiplicity, Use Uncertain States of Europe (Milano 2003); Biomilano: glossario di idee per una metropoli della biodiversità (Milano 2011); L’anticittá (Bari 2011); A Vertical Forest (Milano 2015); La città scritta (Macerata 2016); Urbania (Bari 2021); Green Obsession: Trees Towards Cities, Humans Towards Forests (Barcelona 2021); A private glossary (Rizzoli, 2024) e Bosco Verticale. Morphology of a Vertical Forest (Rizzoli 2024 – Rizzoli NY, 2025)

LUCIJA ŠUTEJ: To begin, I would like to explore the personal foundations of your work. Growing up with an architect and designer mother Cini Boeri, can you share any design philosophies that you and your mother shared? How has her work influenced your research and practice? Additionally, could you highlight specific projects of your mother’s that resonated with you design-wise?

STEFANO BOERI: When you share the same profession as your father or mother, it’s not necessarily a linear transmission of knowledge. It is implicit and a specific approach to the profession of architecture.

In my case, my mother, Cini Boeri, was an architect and a furniture designer. From a certain point of view, what I have done in the beginning was to try at first to avoid studying architecture and I was initially attracted to the ocean and marine biology. However, at one point, I finally understood that my direction was the path of architecture and I moved towards urbanism. The latter is a totally different perspective of the same profession. And I always found it useful - to enter the sphere of architecture from another door. Ultimately, it helped me keep a certain distance from my mother - her skills, talents and influence. To find my own way. What I learned from her was not necessarily about how to design in a linear or academic transmission sense. It was an implicit complicity.

I remember I decided to pursue architecture after a worktrip with my mother to California. We went to visit Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute near San Diego. That vision resonated and brought an understanding of the power of architecture - to bring visibility to things that are not evident.

LŠ: Staying on that thread of shared influences, were there other architects or works that you both admired?

SB: Honestly, no. My mother loved minimalism and Japanese architecture (we met together Kenzo Tange in Tokyo in 1979) and she admired (as I do) the work of Renzo Piano. In the contemporary field, we together met with Frank Gehry, back when I was directing Domus Magazine. I was interviewing Frank (Gehry) and I invited my mother to join me. It was wonderful to see them converse and to see them imagine doing a project together in Sardegna.

My mother was quite skeptical in relation to many of her contemporary colleagues such as Vittorio Gregotti or Aldo Rossi, just to stay in Italy. She was so passionate about a very specific kind of minimalism- where it matches with irony. If you look at her furniture, they are always very simple, and, in my opinion, extremely elegant. However, at the same time her pieces are introducing a joke, a game, and in a way transmitting a paradox. And that was something that was part of that moment of the history of Italian design.

LŠ: You mentioned being drawn to oceanography. I am intrigued by how these early, alternative passions shaped your perspective.

SB: Yes, marine biology and oceanography. I was attracted to the study of oceans for a quite futile reason. I am a fisherman and I love to fish. And when you fish you have to detect and decipher on the surface of the sea, through the waves, what’s happening below. A fisherman has almost a detective gaze that in a certain way it’s not too different from what an architect does.

LŠ: You sparked my curiosity, can we have a question outside the interview structure: where do you usually fish and what?

SB: I started fishing as a young boy. Primarily amberjacks and I only fish in salt waters. And the first question you posed is now coming back in a way. In 1967 My mother built a house in northern Sardinia, on a small island called La Maddalena. this island is very important in my life - even my wife is called Maddalena…She says this correspondence was very important in my decision to marry her (laugh). And it is true (laugh).

Since I was five, I was used to go for a few months to La Maddalena and I used to fish. At the beginning we were renting a small house, but then in the late 60s, my mother built a house for the family, called Casa Bunker (the Bunker House). A concrete building, a few meters from the sea. Living and growing there, learning how to see the landscape from the windows of a bunker building- it became part of my DNA. A part of how I see and experience architecture.

LŠ: I would like to transition to your formative influences and speaking of a specific approach to architecture, I wanted to stop at the impact of the teachings of Bernardo Secchi on your view of urban design? His work directly touched upon the topics such as social inequalities and spatial injustice, which feel extremely relevant.

SB: He was very important for me and the person who helped me move from politics to architecture. As a student, I was very strongly involved in politics, specifically the extreme left movements. As I commenced my studies of Architecture at the Politecnico in Milano, he was then the Dean of Faculty. Under his guidance, I began a study series on the city and the evolutions - politics always has to do with space and the changes around it. Secchi was a very intelligent person and he was really transmitting me the pleasure of intellectual speculation. For me, it was fantastic because I was very curious and attracted to Semiology and Linguistics - some of my research was about how the language of urbanism should be interpreted as rhetoric.

Secchi introduced me to Michel Foucault, a fantastic critical reference and he also taught me how to write, to always work on research first. Back in the 80s, Secchi was one of the unique thinkers in our field that were trying to describe the then ongoing urban sprawl in Europe. He pointed that the urban expansion around Rome, Paris, or Milano pointed towards a crucial understanding of what’s happening in the society. Another of my teachers, Giancarlo De Carlo, also stressed the importance of finding a way to study the relation between space and society, between what’s happening at the surface of the phenomena and below them - economic and social needs, cultural expectations and more. One of my first books, Il territorio che cambia. Ambienti, paesaggi e immagini della regione milanese, co-authored with Arturo Lanzani,and Edoardo Marini, both urban planners, was an inquiry into the urban sprawl of Milano, and the approach we took was basically from Bernardo Secchi’s lesson.

LŠ: Could you tell us about some of your early architectural projects before founding your own firm?

SB: Maybe the most important was a project (Centrale Geotermica Bagnore 3) for a geothermal plant in Tuscany, for Enel Green Power - a national company for electricity. The plant was to be located in Monte Amiata, a very important mountain between Umbria and Tuscany. And the demand was to help with hiding this huge machine. I designed a system of metal, that was Corten essentially. The metal frames were given a new shape, more related with the slope of the mountain, and much more visible in the scenery. Although it was the opposite of what they asked me, They loved the idea and Enel built it.

That was in 1991 and I was also selected and awarded by a jury led by Alvaro Siza and Toyo Ito as part of the best Young European Architect (an Award from Japan) generation . It was an important moment because before I thought of myself more as a researcher and urban planner. Yet, I also wanted to be seen as an architect, but it was quite difficult, honestly, until some years ago. My architect colleagues are, let’s say, 360 degree architects. Coming from an urban planning background - I was always seen as from another sphere. In Italy and Europe, in general, the threshold between urbanism and architecture is still very strong. Which is stupid -and my entire life I considered how to establish a reciprocity between the two.

Boeri Studio, Centrale Geotermica Bagnore 3

Boeri Studio, Centrale Geotermica Bagnore 3

LŠ: This leads perfectly into the founding of Multiplicity, which seems to be the institutionalization of this combined research-and-design approach. Created in 1993 - and what challenges did you face in the beginning? What gap in the international architectural discourse were you aiming to address?

SB: Coming from an urban planning background, I was interested in the idea of producing a kind of local biopsy in the physical urban environment. We observed different European cities. Multiplicity gathered a group of friends such as Francesco Jodice; now a famous photographer, John Palmesino; who’s teaching at AA (Architectural Association - School of Architecture) in London, and more.

Our idea was to focus and study the same local environment from different points of view, always starting from observing what is in real time changing. What made Multiplicity interesting is that there is this convention that if you observe the change you can see what normally you don’t see in urban phenomena. The change is a kind of an explicit expression or a way to make visible what’s happening in the invisible processes that are shaping our spaces.

We did a similar focus with the project Mutations in 2000, when Rem Koolhaas invited us to be part of a wide spread research with OMA in Rotterdam, ETH in Zurich and many other thinkers. We gathered again a network of local researchers focusing on a few European cities - to establish a set of changes.

LŠ: Solid Sea (2002) is a perfect example of the method. Could you elaborate on its impact?

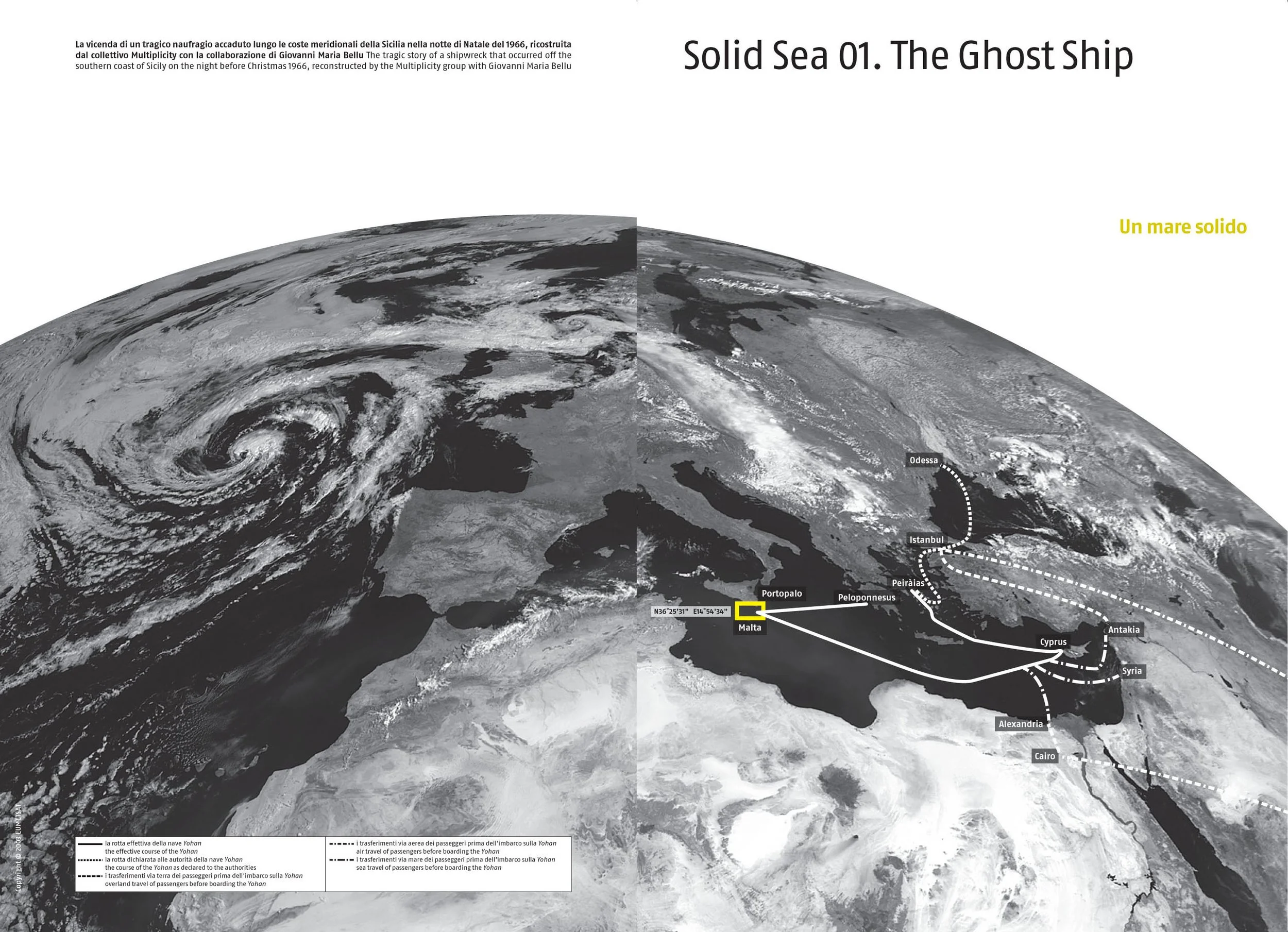

SB: Solid Sea was a very important step for me, not only as an architect, a researcher, but also in my life. All that we now observe happening between North Africa and South Europe, was not at all evident back then. We knew that there had been this tremendous immigration tragedy, happening between Sicily, Tunisia, Algeria and Libya. However, several governments were refusing to talk about it or simply to accept the fact that at that moment in the night there was a tragedy happened in the 1996 Christmas night with a big boat coming from Sri Lanka on the way to Sicily. Due to bad weather, there was a decision to move part of the immigrants from a big boat to a smaller one, and tragedy struck when the two crashed. Hundreds of people dying, at that moment the biggest tragedy since WWII in the Mediterranean sea.

We studied it and went to the scene with a journalist and a filmmaker - to interview the main protagonists of this story - the fishermen, the captain of the big boat, the coastal policeman from Malta and from Italy…. As well as the relatives of the victims and survivors. We presented the project - a journey of the boat, at Documenta XI in Kassel. The theoretical interpretation was that the Mediterranean, instead of being a place of exchanges, of cultural relation, was becoming more and more a solid sea. A solid platform, crossed by ships and boats that have a very strong identity-when you enter the Mediterranean as a tourist, you remain a tourist. When you enter as a soldier, you remain a soldier. When you enter as an immigrant, you remain an immigrant. All these roles are roots, sometimes they cross each other, but they never meet or exchange. So the solidity of the sea is not simply because the sea has become more cruel.

Multiplicity: Solid Sea, courtesy Boeri Studio.

Multiplicity: Solid Sea, courtesy Boeri Studio.

LŠ: This forensic research seems more relevant than before. How do you see the role of research agencies such as Multiplicity in shaping contemporary urban transformations- addressing different social, political, and environmental issues? And their influence on the wider architecture-related discussions?

SB: I see what Forensic Architecture is doing. I met the founder, Eyal Weizman, after the project Mutation. He was so interested in what we were doing, from Solid Sea and Mutation, to Road Map. The latter was a project focused on the border between Israel and Palestine - unbelievably contemporary. We went to the territorial borders of the West Bank, renting two taxis with two taxi drivers. One driver had a Palestinian ID and the other Israeli ID. And we were following with video the route of these two taxi drivers from the same entry point to the same target. One driver spent 1h10 min on the road, while the other about 5h30. And the reason was clear, if you are a Palestinian, you have to pass from different check points with different obstacles, and everything becomes more complicated. An experience of space that was very important.

Collective Multiplicity: Road Map, 2003, still image. Courtesy Boeri Studio.

Collective Multiplicity: Road Map, 2003, still image. Courtesy Boeri Studio.

LŠ: You also mentioned earlier how the language shapes architecture, and here I would like to stop at your role as editor-in-chief of magazines such as Domus and Abitare. How did these roles shape your perspective on architecture and design?

SB: At the start of my career, I was a researcher. Then I worked with Multiplicity, followed by a move to communication (Domus and Abitare magazines), then politics and institutions such as Triennale Milano. Always acting as an architect, hoping to keep this identity strong and current.

I started to run Domus in 2004 and it was fantastic. The way I saw Domus and the challenge was how you could transmit to the readers experiences that they will never have: the experience of entering in a building, touching a wall or seeing how the satellite can change the perception of a space. A space we tried to capture and represent, at a time when paper magazines were still relevant. Now the situation has changed a lot. With Domus, we gathered different cases and points of view. For example, I asked Hans Ulrich Obrist to be our explorer and Bruno Latour to help us to read the images.

LŠ: What do you think is the future of architecture publishing?

SB: There is no doubt that, to answer this question, we must begin with the clear shift underway toward digital-first publishing models. Many architecture magazines are already prioritizing online platforms, reserving print for limited, high-value editions such as award issues, retrospectives, or thematic deep dives. In this context, AI will play an increasingly central role on tailored content —from personalized newsletters and curated content feeds to automated summaries of building case studies and data-driven editorial workflows.

Yet print, in my opinion, is far from dead. In fact, certain niches and historical publications are experiencing a meaningful resurgence. Archinect—originally a digital-only platform—recently launched its print journal Ed, arguing that long-form essays, deep research, and curated portfolios benefit from the tactile, focused environment of the printed page. And magazines like Domus, Detail or El Croquis, even if for experts in the field, still find space on people’s shelves.

When it comes to architecture books, on the other hand, some of these same dynamics apply, but they traditionally emphasize exceptional production quality— rich imagery, large format, high-quality paper. That kind of tactile and visual experience is hard to replace with digital.

However, digital publishing could also open the door to interactive and multimodal forms —embedded media, 3D models, AR, etc. While print will remain essential for monographs, historical surveys, and visual-heavy publications, digital formats can enable expanded content and new modes of engagement.

More broadly, however, the future of architecture publishing must move beyond the traditional model of specialized journals speaking only to professionals. The challenges of our time—climate change, demographic shifts, housing crises, the regeneration of our cities—demand a wider, more inclusive public conversation. Publishing, whether digital or printed, must act as a platform that connects architects, citizens, institutions, and communities. We will see formats that are more interactive, more democratic, and capable of fostering collective intelligence.

LŠ: The Vertical Forest has garnered international attention for its innovative concept - and I would like to turn the focus to its idea as it feels like a synthesis of many of your interests. What impact do you hope it will have on urban sustainability and biodiversity moving forward?

SB: It’s a broad question. (laugh) I think it’s another obsession. We are probably moved by obsessions more than by passions. That’s what I think makes our profession so different from the others - the way we put together research and design, how we study, observe and analyze. With a necessity to see and decide the shape of a space - a configuration of the future. Another passion and active observation, I have had since childhood, are trees.

I always thought that trees are individuals- every tree has individuality, its needs and expectations. This turned into the Vertical Forest. While I was teaching at Harvard University (Graduate School of Design), I was studying the explosion of Dubai, a city in the desert. A city of skyscrapers of glass facades. And I thought about how much energy was consumed. So, I moved towards trees as a way to realize biological buildings as living ecosystems, surrounded and shaded by plants .

Bosco Verticale, drone, September 2018. Courtesy Boeri Studio

Vertical Forest, photo by Giovanni Nardi. Courtesy Boeri Studio.

Vertical Forest, photo by Dimitar Harizanov. Courtesy Boeri Studio

LŠ: Which cities do you see as having the most unique approach to biodiversity?

SB: London could be a first example, due to its national Net Biodiversity Gain policies, which require new developments to deliver measurable improvements in biodiversity. This regulatory framework has pushed the city to integrate nature into the built environment in a systematic and accountable way, setting a strong precedent globally.

Melbourne is another leading example, thanks to a very holistic set of strategies. The city’s “Grey to Green” policy accelerates the conversion of asphalt into expanded footpaths and new public open spaces. Moreover, the “Urban Forest Strategy” aims to increase canopy cover from 22% to 40% over the next two decades – planting roughly 3,000 trees each year not only will expand shade and habitat but also it will increase species diversity and enhances rainwater capture.

Berlin, Rotterdam, and Oslo in my opinion also distinguish themselves through innovative biodiversity plans and nature-based solutions—ranging from green corridors and multifunctional landscapes to climate-adaptive water systems and large-scale ecological restoration embedded in urban development.

Taken together, these cities illustrate how biodiversity can become a structural element of urban planning, rather than an afterthought—each offering a different but equally valuable model for shaping resilient, nature-positive cities.

LŠ: As Vertical Forest points towards the future of permanent, biological infrastructure for cities. In contrast, I also wanted to stop at the current phenomena that is opening another urban future possibility. We have seen a rise in experimental ‘pop-up cities’ like Zuzalu that have new ways of creating community-driven urban spaces. What is your opinion on the impact of these initiatives in influencing permanent urban developments? What challenges and lessons do they present for traditional city planning?

SB: It could be interesting- a family of events or experiences that could be extremely successful. But also sometimes total failures.

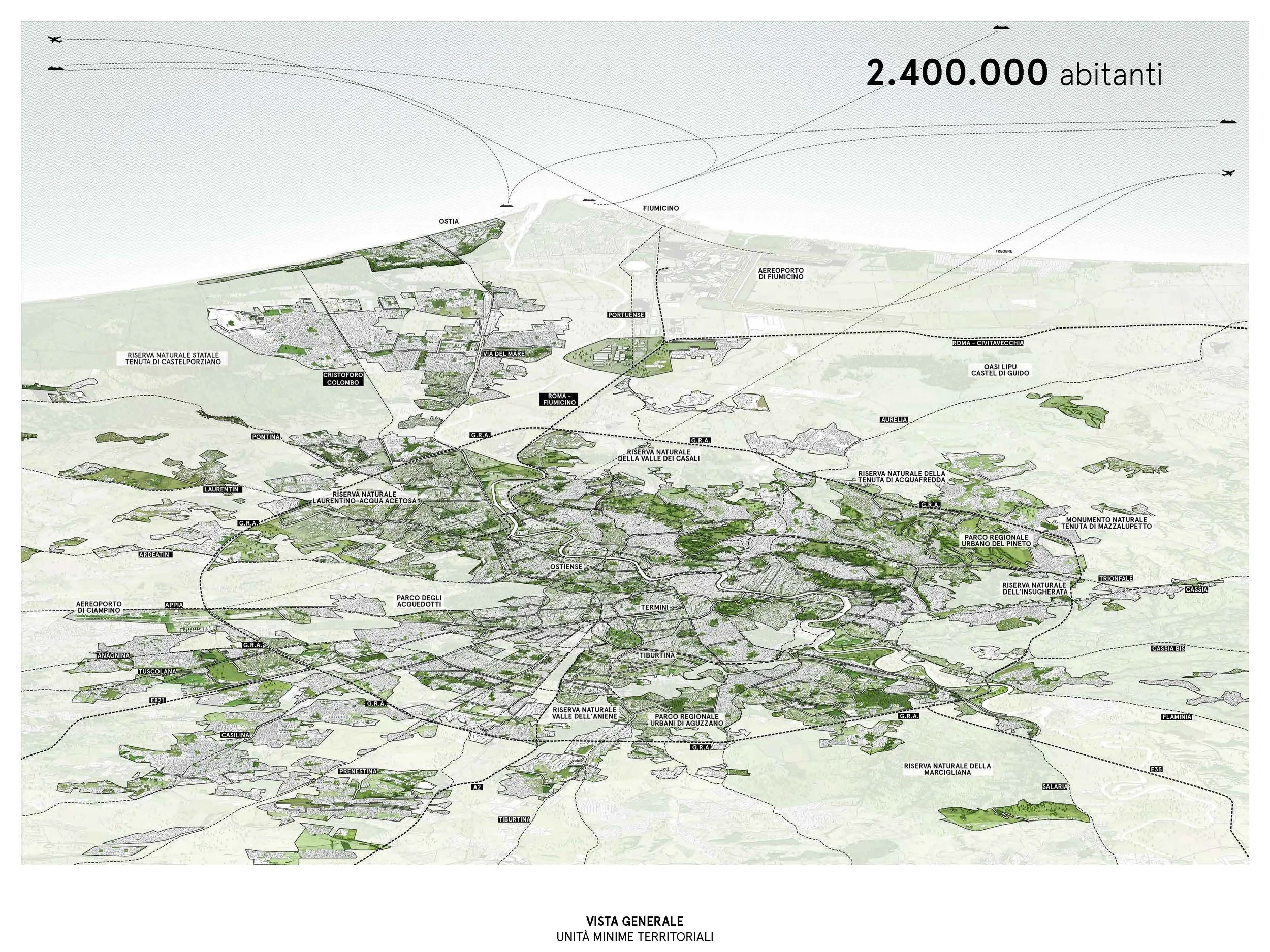

LŠ: You are leading the city- wide laboratory titled Laboratorio Roma050 – il Futuro di una Metropoli Mondo, which envisions the future of the Italian capital. Also called Fresco, it is a vision tool that looks to the year of 2050 and presents two potential systems for the city: Microcities and Metropark or in short - neighborhoods and green areas. If I follow correctly, the project proposes three specific territorial strategies or approaches: the City of Archaeology, the City of GRA (New Green Ring of trees around the capital) and the City of Water.

Could we hear more of the programme and its vision - its structure and the individual layers of the city?

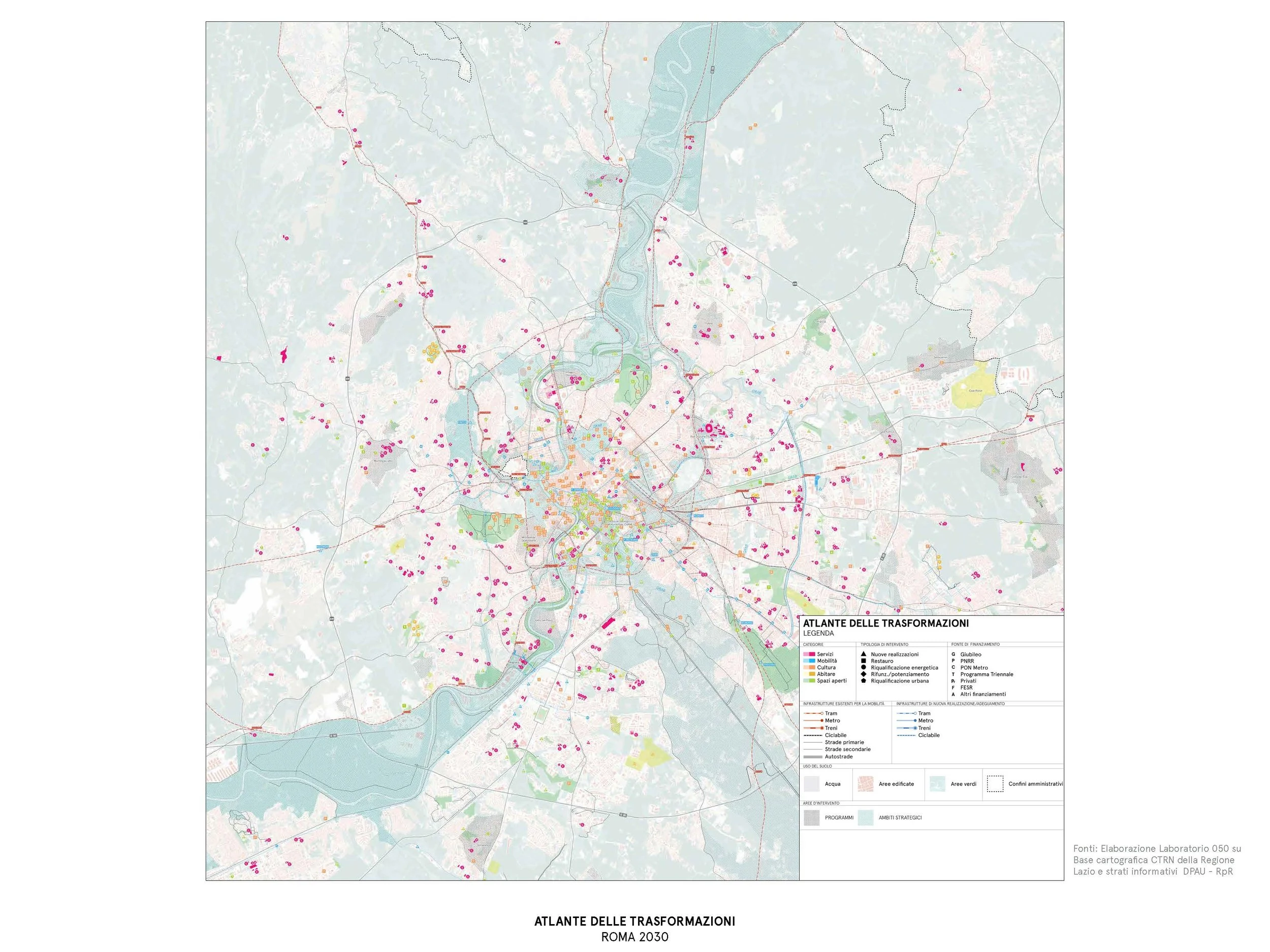

SB: Yes, we had the incredible opportunity to do a vision for the future of a large, impressive and unique metropolitan environment. We are studying the city in three different chapters. It’s not a chronological sequence, but in a certain way it could be. The first part was an Atlas, a collection of changes, processes and transformations. From this point of view what we had done in Roma was to observe all the projects that were changing the condition of the city: different stakeholders, investment -both private and public, etc.

This first part of the project focused on the first five years (2025-2030), while the second chapter lined out a more strategic vision of possibilities for the future (2030/2050) that can be found starting from the present conditions. Rome is a massive city that is composed of so many small cities, micro communities and a network of organic and permeable lands. So, here we see all the different layers that make Rome - a kind of metropolitan archipelago. For example, we are working on the idea to transform this huge orbital highway into active infrastructure for the new city, with institutions supporting crafts, university research and high-tech industry.

Another vision is for the river, Tiber, and the city of Ostia. Currently quite abandoned, however, in our vision it becomes the entrance to Rome or the door to the megacity. We looked from various perspectives to the river - from the angle of the Mediterranean, from the Tyrrhenian Sea, etc. to see how we could make changes along the river.

And another level is focused on archeology in partnership with the archeological department of Sapienza University of Rome. Rome could become a truly active archaeological site, with excavations taking place everywhere — not only in the historic center, but also inside building walls, near the orbital highway, and even beyond it. The city holds an extraordinary wealth of potential discoveries that is still largely invisible. Rome is a unique world, where the density of historical legacy and cultural heritage is unlike anywhere else.

Atlas of Transformations, Rome 2030. Courtesy Boeri Studio.

General View, Minimum Territorial Units. Courtesy Boeri Studio.

Widespread Archaeology as a Cultural, Educational and Economic Resource. Courtesy Boeri Studio.